In this ardent article, Tommaso Priviero explores Dante’s Commedia as a visionary journey shaped by love, and shows how C.G. Jung encountered in it a living model for his own descent into the unconscious. Moving between fire and form, eros and logos, his analysis culminates in love as an enigma rather than a dogma: a primordial force that animates visions, demands surrender, and calls the “I” to become the servant of the soul.

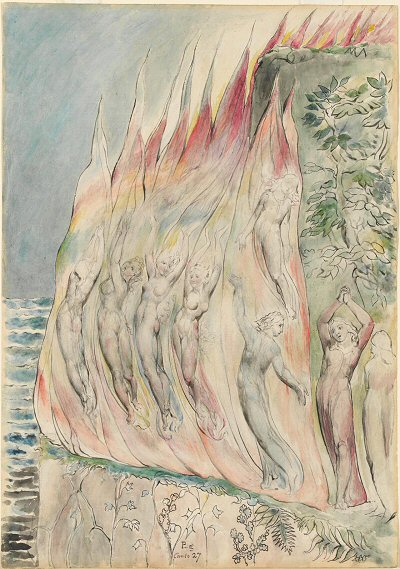

Dante at the Moment of entering the Fire by William Blake.

On this page

- Primal love

- The most difficult experiment

- Jung’s Dante

- Dante in the Red Book

- Love-episodes

- Becoming new

- Mysterium

- Purgatorio, XXX

- The lady of the mind

Primal love

At the beginning of the Commedia, Dante has just survived a night of terror in a dreadful dark forest. He wakes up in a wasteland, surrounded by three ferocious beasts. He cannot go back, he cannot go forward. He admits he has no clue about where he is and why he is there. He is lost and hopeless.

A luminous figure, the Roman poet Virgil, appears in front of him, offering guidance. He tells Dante that if he wants any help, he will have to take another path.

It is another path that you must take. (Inferno, I, 91)

Dante has no choice. He accepts the invite and follows his protector, like a shivering child. Virgil tells him that he has been sent to him as the servant of a “higher spirit”, whom Dante might be able to meet, when the time will come. Before that moment, other experiences are necessary.

Virgil takes Dante by the hand and conducts him to the gates of hell, where a famous inscription welcomes the visitors:

Through me the way into the suffering city,

Through me the way to the eternal pain,

Through me the way that runs among the lost.Justice urged on my high artificer;

My maker was divine authority,

The highest wisdom, and the primal love.Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope, who enter here. (Inferno, III, 1-9)

The Gates of Hell by Auguste Rodin (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Among these verses of blackness and despair, one appears in contrast with all others: “The highest wisdom and the primal love”. The word “love” right where it would be expected the least: the inscription of the gates of hell.

This very same line appears around January 1914 in Black Book 4, during a crucial phase of Jung’s own “season in hell”, which was documented in a manuscript entitled Liber novus, commonly known as Jung’s Red Book.

The verse was copied directly in Italian by Toni Wolff, in her handwriting. She was the only other person who was allowed to write in Jung’s notebooks during this delicate phase.

The most difficult experiment

Jung considered the Red Book no less than the most difficult and most important “experiment” of his life and the source of his entire psychological system. Invariably, the publication of the Red Book in 2009 and the Black Books in 2020 set forth a revolution in Jungian studies. Unexplored topics emerged following these publications. Among them is the key role that Dante and the Commedia played at the heart of Jung’s self-explorations.

There is something unique about Jung’s encounter with Dante. Unlike other examples, the Commedia provided Jung not only with a model for a journey to hell, but also and especially, with the guidance for creating a process of psychological rebirth.

This particular aspect was captured by the medical historian Henri Ellenberger in his seminal work The Discovery of the Unconscious:

One characteristic feature of any journey through the unconscious is the occurrence of what Jung called enantiodromia. This term, originating with Heraclitus, means the “return to the opposite”. Certain mental processes are turned at a given point into their opposites as if through a kind of self-regulation.

This notion has also been symbolically illustrated by poets. In the Divine Comedy we see Dante and Virgil reaching the deepest point of hell and then taking their first steps upward in a reverse course toward purgatory and heaven.

This mysterious phenomenon of the spontaneous reversal of regression was experienced by all those who passed successfully through a creative illness and has become a characteristic feature of Jungian synthetic-hermeneutic therapy (Ellenberger, 1994, p. 713).

What Ellenberger did not know is that Jung actively read the Commedia while composing the Red Book.

Jung’s Dante

Jung read Dante in a German edition given to him by his aunt in 1898, when he was twenty three. The book presents signs of frequent reading, annotations, and various slips of paper next to significant passages (Priviero, 2020).

He read Dante throughout his entire life, with an increasing interest in three figures of the Commedia:

- Lucifer, the symbol of a chthonic trinity (umbra trinitatis) which called for integration within the one-sidedness of the Christian godhead;

- Beatrice, which in Psychological Types he described as a beautiful symbol of the modern man’s search of the “soul”;

- the mystical rose, which he considered a Western mandala, a symbol of psychic totality, equivalent to the lotus of the East.

These motives appeared in many forms in Jung’s scientific works.

In parallel, he became deeply interested in the so called “esoteric” or “symbolist” interpretation of Dante, which was evolving in Europe around that period. The only major commentary on Dante in Jung’s library in Küsnacht was the most important text within this tradition, a German translation of Luigi Valli’s Il linguaggio segreto di Dante e dei Fedeli d’Amore [The Secret Language of Dante and the Fedeli d’Amore].

At the core of this tradition was the view that the Commedia was not only a great literary or theological work, but essentially the documentation of a first-hand experience of visions, which was communicated among the members of an esoteric group of poets known as the Fedeli d’Amore or “Poets of Love”.

The esoteric Dante engaged major intellectuals involved in the study of European symbolism such as W. B. Yeats, E. Pound, H. Corbin, M. Eliade, R. Guénon, J. Evola, and Jung, who in a passage of Psychology and Poetry claimed that the historical and literary layer of the Commedia was merely a “cloak” to disguise the “real” and “deeper meaning of the work”, which lay in the powerful “visionary experience” it served to express (Jung, 1930/1950, p. 143).

This view drew Dante to the tradition of the medieval “meditation books” or “books of visions”, such as John the Monk’s Liber visionum or the Ars Notoria of Solomon. These texts were autobiographical notebooks which recorded the inner experiences of medieval visionaries. They used notae, i.e. images next to the text, diagrams or words in elementary geographical shapes, which provided focal points for meditation while the texts were being recited in contemplation. They described the travelling of the authors to “the other world” and the self-transformation which then occurred.

Dante in the Red Book

Fascinatingly, until the 16th century, Dante’s Commedia was known in the English world as The Vision of Dante. What Dante’s “vision” entailed was thus understood by T.S. Eliot:

Dante’s is a visual imagination. It is a visual imagination in a different sense from that of a modern painter of still life: it is visual in the sense that he lived in an age in which men still saw visions. It was a psychological habit, the trick of which we have forgotten, but as good as any of our own.

We have nothing but dreams, and we have forgotten that seeing visions—a practice now relegated to the aberrant and uneducated—was once a more significant, interesting, and disciplined kind of dreaming. We take it for granted that our dreams spring from below: possibly the quality of our dreams suffers in consequence (Eliot, 1965, p. 15).

Jung’s view of the Commedia as a “visionary experience” explored a similar perspective. However, first and foremost, it was a direct consequence of Jung’s own “visionary experience”, that is, the material that formed the Red Book. Although Dante featured on multiple occasions in Jung’s psychological works, it was nowhere as important as in the Red Book.

As early as December 26, 1913, about a month after the beginning of his experiment, Jung copied together in Black Book 2 the following citations from two different Cantos of Dante’s Purgatorio:

I am one who, when Love breathes

in me, takes note; what he, within, dictates,

I, in that way, without, would speak and shape.And then, just as a flame will follow after

the fire whenever fire moves, so that

new form becomes the spirit’s follower. (XXIV, 52-54, XXV, 97-99)

These lines convey the core of Jung’s encounter with Dante. The combination of “fire” and “form” offers a remarkable poetic synthesis of Jung’s method to make sense of his experiences. “Fire” represents the psychic energy of the visions and “form” a space to host them “whatever shape it takes”, that is, whichever direction these visions take.

“Fire”, for Jung, alluded to the vital and dangerous force of the passions and “form” to the difficult art that is required to harness them. These entries evoke the sacrifice of the ego-view to a greater force of inspiration with transformative effects upon the subject’s mind.

As different degrees of the same substance, the individual self, the “flame”, is put at the service of a deeper energy, the “fire”, the consistency and effects of which have to do with the enigmatic action of love. That same action which is referred to at the gates of Dante’s hell and which seems to imply that through love, even hell, sometimes, can be traversed.

Love-episodes

Dante’s love can be traced back about seven centuries ago, when he met a young girl from Florence dressed in scarlet red: Beatrice Portinari. Not much is known about this woman, except that she was probably the daughter of the Florentine banker Folco Portinari.

What is known for sure is that Dante fell in love with her instantly. He had dreams and visions about her and he often felt his tongue composing poetry “by moving almost of its own accord”.

Unfortunately, Beatrice died at a very young age, causing Dante tremendous suffering. In the pages of the Vita Nova, he described the intention to overcome that unbearable pain through an ambitious deliberation: to “write of her that which has never been written of any other woman” (Dante, 1977, p. 74).

Nevertheless, in the following years Dante forgot his promise. He committed himself to unfortunate political activities that sentenced him to perpetual exile from Florence and charges of heresy from the Church. Around the midpoint of his life, Dante was in such turmoil that he described finding himself in a near-death state, in the middle of a dreadful forest.

Then he finally remembered his vow. Irma Brandeis noted that Dante “has not so completely forgotten Beatrice that she cannot rescue him” (Brandeis, 1962, p. 119).

Therefore he embarked on a journey to the underworld to find his beloved again, which forms the plot of the Commedia.

In Psychological Types, Jung pointed out that the birth of modern European individualism occurred in the late Middle Ages through the symbol of the “worship of the woman”, adding that:

This is nowhere more beautifully and perfectly expressed than in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Dante is the spiritual knight of his lady; for her sake, he embarks on the adventures of the lower and upper worlds (Jung, 1921, pp. 376-377).

In Psychology and Poetry, he also noted that “visionary works” such as the Commedia, Goethe’s Faust, or the Shepherd of Hermas, pointed to a direct connection between love and visions.

For Jung, the visionary experience was the culmination of a “preliminary love-episode” of some sort.

He said:

The love-episode is a real experience really suffered, and so is the vision (Jung, 1930/1950, p. 148).

The vision had in itself “psychic reality” and this was “no less real than physical reality”.

The experience of love, he argued, was the fundamental prerequisite of “a tremendous intuition that strives for expression”.

Jung was personally involved in a similar quest. As now historically confirmed following the publications of the Red Book and the Black Books (Shamdasani, 2009, 2020), Jung’s visionary endeavors were also crucially affected by “love-episodes”.

On the one hand, he repeatedly stated how the fact of being a husband and father decisively helped him deal with and survive the material of the Red Book. In June 1917, after an ecstatic vision in the Swiss Alps, Jung unequivocally wrote to Emma: “I want to cling to you, since you are my center, a symbol of the human, a protection against all daimons” (Jung, 2020, p. 69).

On the other hand, Jung found in his lover and collaborator Toni Wolff an indispensable presence through the years of his experiment and beyond.

In a Dantesque fashion, Toni Wolff acted like the soror mystica (the “mystical sister”) who guided and shielded Jung through his self-explorations. He felt that his and her fantasies were part of a common stream and gratefully acknowledged her presence and insight.

Her personal copy of Psychological Types bore this dedication: “This book, as you know, has come to me from that world which you have brought to me. Only you know out of which misery it was born and in which spirit it was written” (Jung, in Shamdasani, 2020, p. 97).

Jung’s thoughts on love were not an intellectual abstraction. As evoked by his entries on Dante in the Black Books, love was a living force “dictating” the writing of the Red Book.

Becoming new

It is especially significant that Jung chose his Dantesque entries from the Canticle of Purgatorio, which means “purification”, from Greek “pur”, “fire”. As Barolini wrote, Dante’s Purgatorio is the place where “everyone is working on becoming new again” (Barolini 2014, p. 19).

In Dante’s visual construction, purgatory was a mountain caused by Lucifer’s fall to the bottom of the Earth after his rebellion against God, which formed an exact geometrical counterpart to the abyss of hell. Dante calls it the holy “mountain which / purifies as one climbs it” (Purgatorio, XIII, 3).

Approaching this mountain, Dante’s Odysseus, in Inferno XXVI, drowns in a terrible sea storm (a Dantesque invention). In contrast, Dante survives the same voyage and so he is granted the ascent to heavenly skies, because, as noted by Borges, he was able to surrender to the guidance of “higher powers” (Borges, 1999, p. 281).

Purgatory is a second kingdom between hell and heaven. It encapsulates the ideas of intermediacy and liminality. However, as Le Goff noticed, it is not a “neutral intermediary but an intermediary with an orientation” (Le Goff, 1990, p. 337), bridging these two realms. Purgatory is the place of self-transformation. And purgatory is the realm where Dante can meet Beatrice again and part ways from Virgil.

In 1917-1918, the Swiss psychoanalyst Alphonse Maeder gave two talks on “Healing and Transformation in the Life of the Soul”, one of which was at the Association of Analytical Psychology, in Jung’s presence. In this context, Maeder compared the Commedia to psychoanalytic work.

The descent to Hell represented the conflicts of the past; the second half of the journey, which began in Purgatorio, corresponded to the future, the teleological movement. Hell was a paralysis of the vital energy, purgatory was a “work of purification”, which tended towards an “upward progressive movement, a channeling and application of mobilized energies” (Maeder, 1918, p. 35).

Jung commented at that time that Maeder’s parallel with Dante was an excellent “educational introduction to analysis” (Minutes of the Association of Analytical Psychology, Sonu Shamdasani’s personal communication).

Many years later, in his 1930-1934 seminar on Christiana Morgan’s visions, he took up this parallel and made a significant reference to the symbol of fire in Dante’s Purgatorio:

People are afraid of the fire of passion and then passion seizes them. They think it is a mistake, but they need and are really looking for it; and the more they know, the less they will deny passion. They will accept it because they know it is the purifying fire that is needed for the production of the pure gold.

So to get into a purified condition one must pass through the zone of fire in which every desire is burned out, the result being worthless ashes blown away by the wind, and the pure gold that stands the fire forever. There is a beautiful expression of that symbolism in Dante’s Divine Comedy. In the last circle of purgatory, when approaching the celestial sphere, Virgil leads Dante to the flame of purification. […]

You see, this symbol is a psychological experience, and it shows itself in the form of a continuous machine-gun fire of emotions which in the end die down, and one would say the fire had burnt out, that it was a burnt-out crater; and externally, or if one looks at it superficially, one might see it as complete destruction, with nothing left.

But if one goes down into the crater, at the bottom one finds the gold, the valuable substance which is no longer touched by fire, and this is the meaning of all the nonsense that went before (Jung, 1997, p. 1055).

Later, he reiterated:

Dante had to pass through that pure flame in which all earthly admixture, all ego desirousness, was burned out of him. That would be the sacrificial fire, and only the one who has passed through that fire can be absolutely whole and strong and enter the supreme condition (Jung, 1997, p. 1107).

These references bring us right back to the fiery time of Jung’s experiment.

Mysterium

As said above, it was nearly Christmas 1913 when Jung decided to copy two entries from Dante’s Purgatorio in his notebooks. Around this time, he recorded one of the most important episodes in the entire Red Book: a section entitled “Mysterium” (a word which in ancient Greek meant “mystery”, but more specifically “secret ritual”) (Jung, 2009, pp. 245-254).

Right before this vision took place, he noted that his method of internal visualisation and dramatized dialogues with personified characters was pushing him deeper and deeper into his unconscious mind. There he caught a glimpse of cosmic depth which took the form of a giant volcanic crater, reminiscent of Botticelli’s famous representation of Dante’s Inferno.

A conflict arose in him between the desire to continue his mental journey and a resistance to going further down. This conflict was ominously portrayed in Black Book 2 as the battle between the “serpent of the night” and the “serpent of the day”.

Soon afterwards, Jung’s “I”, the narrator of the Red Book, becomes the protagonist of a ritual of initiation, guided by two figures: the prophet of the Old Testament Elijah and the princess-enchantress Salome, the granddaughter of Herod the Great.

A serpent coils around the body of Jung’s “I”, while Elijah mysteriously asks him to worship the blind Salome. The “I” is horrified by this request and bursts out in tears. Only when he finally surrenders to love Salome “in wonderstruck devotion”, the serpent uncoils from his body and the blind woman gains sight anew. This time tears of joy appear on the face of Jung’s “I” and an extraordinary feeling of psychic renewal is unleashed.

Although this cryptic scene has been analyzed before, not much has been said about its striking correspondences with the Commedia.

First of all, the landscape of the episode deserves attention. In Jung’s vision, the “I” finds himself at the “foundation of the crater in the underworld”, while a “huge mountain” grows upwards, where the “house of the prophet” Elijah resides. In 1925 Jung commented that this image was informed by the same archetypes, “as above so below”, which inspired Dante’s Commedia.

McGuire noted that Jung was referring to the mirroring correspondence between Dante’s circles of Hells and skies of Heaven, but it is more correct to think about it in terms of the connection between the crater of the underworld and the mountain of purgatory.

There is more to be said on this point. At the end of the initiation, Jung’s “I” feels so blissful that he hurries out of the darkness of night with his feet off the ground, melting into air. It is a moment of great transformation, which also meaningfully marks the end of Liber Primus, the first of the three parts forming the Red Book.

At the end of Dante’s Inferno, the first of the three Canticles of the Commedia, similar events take place. After reaching the greatest depth of the Earth, Dante has to climb up Lucifer’s legs, hurrying out of a last night in hell. Since Lucifer is graphically stuck at the centre of the Earth with his legs up in the air, the act of climbing over his body forces Dante to turn his vision upside down, in order to be able to come out in the opposite hemisphere. Thus Dante throws his arms around Virgil’s neck and they begin to climb over Lucifer’s body, gradually moving out of darkness and towards “brighter worlds”, i.e., purgatory.

The entire passage at the end of the Inferno was underlined in Jung’s personal copy of the Commedia, including a piece of paper to mark the page.

When Virgil tells Dante that they are ready to move on, a hole opens through the rocky depths, letting light come in, like an invisible door into a new level of perception. Similarly, Jung used the image of “boring through” the crater to describe the visualisation technique that provided the material for the Red Book, and referred to it as the act of digging a mental hole through which light could pass (Jung, 2012, p. 51).

The second correspondence concerns the directionality of this eventful transformation. Both Jung and Dante refer to the left as the side of the unknown.

“Sinister” is the Latin word for “left” in many European languages. Dante’s descent through the rings of hell occurs by always keeping to the left while going towards the bottom. So Dante remains on the side of Virgil, who leads the way while protecting him.

The poet

kept to the left, and I followed him (Inferno, XVIII, 20-21).

However, when Virgil and Dante begin their ascent of the mount of purgatory, the direction is inverted, going upwards towards the right and gaining light at each step. There is only another moment in Purgatorio in which Dante turns to the left again. It is when he looks at Virgil for a last time before encountering Beatrice.

Similarly to Dante, in the Black Books Jung speaks of the images appearing from the left, such as the apparition of Salome, as having a hell-like quality, emerging from the side of the “unholy, unknown and inauspicious”. The left is the abode of instincts, wilderness, and things that are yet to be, into which one can only go, as Jung wrote, “without purpose and intention”:

Since Eros poses the most serious problem at first, Salome enters the scene, blindly groping her way toward the left. […]

The left is the side of the inauspicious. This suggests that Eros does not tend toward the right, the side of consciousness, conscious will and conscious choice, but toward the side of the heart, which is less subject to our conscious will.

This movement toward the left is emphasized by the fact that the serpent moves in the same direction. The serpent represents magical power, which also appears where animal drives are aroused imperceptibly in us. They afford the movement of Eros the uncanny emphasis that strikes us as magical.

Magical effect is the enchantment and underlining of our thought and feeling through dark instinctual impulses of an animal nature. The movement toward the left is blind, that is, without purpose and intention. It hence requires guidance, not by conscious intention but by Logos (Jung, 2009, p. 366).

In his psychological works Jung examined this motif in depth, including, among others, a reference to the “circumambulation” from the left in one of Wolfgang Pauli’s dreams. However, this annotation lets something else emerge. The left is not only the side of the uncanny and the unknown. The left is also the “side of the heart”, the side of eros and love.

And around an act of love seems to revolve the key to Jung’s mystery play. “Must I love Salome?”, the narrator asks himself.

When Salome is initially not welcomed by the “I”, she manifests herself as blind irrational desire. A “horny” and “bloodthirsty” demon which in Black Book 7 Jung describes as follows:

She makes one drunk and she is drunk from the blood of the holy one, she pours poison into the entrails. She is a fire of voluptuousness and torment of voluptuousness. She is beautiful like hell. She gives pleasure and the craving for poison. She makes men drink poison and eat poison. She is hellish temptation (Jung, 2020, pp. 186-187).

The “I” then urgently poses this question: “How can I release her?” A little later, Salome herself offers a solution to unravel the riddle: “He who fights against me fights against himself” (ibid., p. 188). A painful sacrifice is required, which entails a wound to the hero-driven perspective of the “I”. Only as long as the narrator learns the art of loving Salome, this dangerous symbol can acquire new life and sight.

In this process, Jung describes a clear shift of gravity from the sense of fighting a demon, to the one of feeding it.

This transformation is also announced by a significant linguistic change. At the beginning of the “Mysterium”, he speaks of Salome’s power in terms of “blind” desire. At the end, he begins to call it eros.

Neither purely sensual eros nor a psycho-intellectual simulacrum devoid of life. Rather, a living force permeating all things in nature.

This is a primordial version of the myth of eros which appeared since Hesiod’s Theogony, but became gradually relegated in Western art and literature either to a Platonic ideal of love or to the reassuring image of the winged boy Cupid.

The eros of the Red Book points in a different direction from both. It is sometimes represented as Phanês, a primordial god of light and creation. In a book published around the same time as the years of the Red Book, the German philosopher Ludwig Klages immortalized this “cosmic eros” as follows:

Eros is called elemental or cosmic in as far as the individual in the grip of Eros feels as if he is pulsing and flooded through with a kind of electrical current which, similar in essence to magnetism, makes the most distant souls sense a mutual conjoining pull irrespective of their limits.

Eros is the essence of all happening, which separates the bodies, and which transforms space and time into the omnipresent element of a sustaining and engulfing ocean thus joining together the poles of the world (Klages, 2018, p. 111).

Purgatorio, XXX

In Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung claimed that visionary experiences were typically regulated by “two archetypes”: the “wise old man” that personified “meaning” and the “anima” that expressed “life” (Jung, 1955, p. 313).

Long before this formulation, Elijah and Salome represented the first variant of a combination of opposite forces that accompanied the Red Book in its entirety. As “eros” and “logos”, Salome is pleasure and “fire”, Elijah thinking and “form”. In Jung’s vision, they are connected through a third principle, the serpent:

Forethinking is not powerful in itself and therefore does not move. But pleasure is power and therefore it moves. Forethinking needs pleasure to be able to come to form. Pleasure needs forethinking to come to form. […]

The way of life writhes like the serpent from right to left and from left to right, from thinking to pleasure and from pleasure to thinking. Thus the serpent is an adversary and a symbol of enmity but also a wise bridge that connects right and left through longing, much needed by our life (Jung, 2009, p. 247).

When balance between the two is achieved, Jung argued, both principles become one “in the symbol of the flame”. In the process, Elijah evolves into the figure of Philemon, the Virgil of the Red Book, whose name comes from the Greek verb “to love”. And Salome sets up the most challenging task of Jung’s explorations, that is, learning to love the “soul”.

One principle provides the energy that is necessary to experience the journey. The other principle conveys the containment that is needed to survive it.

Following this track, a similar encounter of opposites take place in the Commedia, particularly in Purgatorio, Canto XXX. After strenuous trials, Dante is finally approaching the moment which Virgil announced to him at the beginning of the journey, i.e., the encounter with Beatrice.

I’ll leave you in her care, when I depart (Inferno, I, 123).

Borges considered this moment “one of the most astonishing” scenes that literature has ever achieved. The passage deserves another reading:

A woman showed herself to me; above

a white veil, she was crowned with olive boughs;

her cape was green; her dress beneath, flame-red.Within her presence, I had once been used

to feeling—trembling—wonder, dissolution;

but that was long ago.Still, though my soul,

now she was veiled, could not see her directly,

by way of hidden force that she could move,

I felt the mighty power of old love.As soon as that deep force had struck my vision

(the power that, when I had not yet left

my boyhood, had already transfixed me),I turned around and to my left—just as

a little child, afraid or in distress,

will hurry to his mother—anxiously,to say to Virgil: “I am left with less

than one drop of my blood that does not tremble:

I recognize the signs of the old flame.” (Purgatorio, XXX, 31-54)

Seven centuries after this occurrence, the expression “conosco i segni de l’antica fiamma” (“I recognize the signs of the old flame”) can still be used in Italian to designate the occurrence of falling in love.

Dante turns to the left again and looks at his “sweet father” Virgil for counsel. But the master is silent, the poet needs to proceed on his own, along with Beatrice.

It has been noticed that the figure of Jung’s Philemon in the Red Book presents traces of both Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Dante’s Virgil. My colleague Gaia Domenici has brilliantly analysed the role of Zarathustra in relation to Philemon in her book Jung’s Nietzsche (Palgrave, 2019). A question then arises about the difference that the models of Zarathustra and Virgil offered to Jung. Essentially, this seems to revolve around love.

In Jung’s problematic interpretation of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the German philosopher was described as a case of “inflation”, that is, a thinker who identified with the archetype of the “wise old man” (Zarathustra) and ended up dramatically splitting from earthly endeavors such as sensation, sexuality, feelings, and the normality of everyday life.

In Jung’s reading, Nietzsche became possessed by a power fantasy (philosophically formulated as the “Will to power”, one of the central tenets of Nietzsche’s system) which ultimately shattered his brain. The main problem, Jung argued, while discussing the scene in which Zarathustra dances as Salome, comes all from the fact that:

we have no anima in Zarathustra. […] We have here the most perverse phenomenon, the wise old man appearing as identical with Nietzsche himself without the anima (Jung, 1988, p. 533).

If one accepts Jung’s point of view, it can be argued that the Commedia features the opposite phenomenon. Purgatorio XXX announces that a differentiation between master and disciple is possible. Virgil is the type of guide who binds “lower” and “upper” worlds. He is the psychopomp who knows how to enter hell but especially how to find a way out. And first and foremost, from his first appearance, he is presented as Beatrice’s servant.

Zarathustra teaches Nietzsche will to power, Virgil instructs Dante in the things of love.

The lady of the mind

Auerbach observed that the distinctive trait of Dante’s poetry was its “visionary realism”. Many poets of the Middle Ages, he wrote in 1929, had a “mystical beloved” and “had roughly the same fantastic amorous adventures” and “belonged to a kind of secret brotherhood which molded their inner lives and perhaps their outwards lives as well”, but “only one of them, Dante, was able to describe those esoteric happenings in such a way as to make us accept them as authentic reality” (Auerbach, 2007, pp. 60-61).

Purgatorio XXX stands out as an excellent example of visionary realism. While reading the passage, then as now, a precious intuition surfaces. That before the complex construction of the Commedia, the final ecstasy, the countless characters and stories, the piles of commentaries and disputes, the glory to which the work will be destined for centuries, a more primordial element arises.

Before all this, the episode that the entire story originated from bears the unmistakable signs of an experience of love.

The object of love has now transmuted into another dimension. It has become a “purely psychological factor”, as Jung wrote of Beatrice in Psychological Types (Jung, 1921, p. 377). Yet, the flame of the experience of love belongs in the same fire, Dante tells us. No matter how hidden its form, Beatrice illuminates the poet’s mind.

And despite some calling Beatrice a glorious literary invention or a metaphysical allegory, the subtle reality of her presence in Dante’s mind transcends by far the limits of fiction. In fact, as Dante presents her to the reader, Beatrice has never been so shockingly real as she appears now to the poet’s mind.

Her pivotal effect is epitomised by the first words that she uttered to a frightened Dante in the entire Commedia (words which Ezra Pound counted among his favorite lines) (Inferno, II, 70-72):

For I am Beatrice who send you on;

I come from where I most long to return;

Love prompted me, that Love which makes me speak.

Just as eros “moves” Jung’s visions (“Forethinking is not powerful in itself and therefore does not move. But pleasure is power and therefore it moves”), love makes Dante move on. That love which prompted Beatrice to rescue the poet, mediating between outer events and inner reality.

Since for the visionary what is imagined is real, the imagined reality of his love for Beatrice knows no limits. Virgil leaves the scene at this point because, apart from being a heathen who cannot enter Dante’s Heaven, the “wise old man” cannot teach much about the practice of love.

When it comes to the things of eros, in fact, it is Diotima, in Plato’s Symposium, who instructs Socrates on things he does not know about. Similarly the sighted Salome gives life to Jung’s visionary process. It encapsulates what Neumann, in The Great Mother, called the most distinctive trait of the feminine, i.e., the “transformative” quality (together with the “elementary” quality) (Neumann, 1955, p. 24).

That dynamic part of the psyche (psyché, in Greek, itself a feminine word meaning “breath” or “life”) which “drives towards motion, change, and transformation”. The “vehicle par excellence of all the adventures of the soul and the spirit, of action and creation in the inner and the outer world” (Neumann, 1955, p. 24).

Traditionally, this topic is linked to Jung’s discussion of the “anima” archetype. And there is no doubt that, during the years of his experiment, he repeatedly tackled the “anima” problem in his psychological works, in close relation to the Middle Ages and Dante.

Nevertheless, in the records of the Red Book, the word “anima”, as in Jung’s psychological use, does not technically appear, except for a couple of mentions in the Black Books in the 20s.

The “anima” in its strict sense pertains to a different vocabulary from that of the Red Book, in which later Jungian terminology finds little or no place at all. What one finds instead is the “Seele” or the “anima” in its broad meaning, i.e., the “soul in the primitive sense” (Jung, 2009, n56).

From the start of his experiment, Jung’s soul takes on the voice and the appearance of a “She” or, to use a Dantesque expression, a “lady of the mind”. As Dante returns to Beatrice after many years of wandering, the narrator of the Red Book claims to have returned to his soul “like a tired wanderer who had sought nothing in the world apart from her” (Jung, 2009, p. 233).

Interestingly, he does not claim to discover the “anima”. Rather, he claims to return to her. He says that he “spoke” and “thought” and “knew many learned words” for her. He says that he “judged her” and “turned her” into a scientific object. So he did not consider that the soul cannot be the object of judgment and knowledge.

A dramatic reversal of perspective takes place in the Red Book. The “I” is compelled to become the servant of the soul and the sole measure of his freedom is his capacity to love her.

Accordingly, the faces of the soul in the Red Book are as many as Jung’s encounters with her: she is a “child”, the “soul of a woman”, the young daughter of an old scholarly man, being held in captivity in a castle, a demon, a murdered young girl (in “The Sacrificial Murder” scene) who turns into a beautiful maiden with ginger hair, a high priestess, a destructive force, a serpent who turns into a white bird that lays a golden crown in Jung’s hands, and others.

Common to all these different faces, however, is one fact. The narrator is urged to learn an art of loving. Because the “knowledge of the heart”, as Philemon reveals to Jung’s “I”, “is in no book and is not to be found in the mouth of any teacher” (Jung, 2009, p. 233).

The word love appears hundreds of times in the Red Book. In its first mention, in 1913, it is directly addressed to the soul. Love is the capital word of the “Mysterium”, the puzzling connection between the “I” and Elijah and Salome (“Must I love Salome?”).

Love is especially present in the records between November 1913 and April 1914, when Jung’s love relationship with Toni Wolff was unfolding. A large portion of the Black Books and the Red Book was composed during this period.

Love (“Amor”) is the word that inspires the entries from Dante’s Purgatorio in the Black Books. And most importantly, in conclusion, love was for Jung an enigma (a word which can be thought of as the opposite of “dogma”). An enigma in front of which imagination fails and silence prevails, as Dante wrote at the very end of his journey.

December 2025

For those who would like more information on this topic, see the presentation of Tommaso Priviero’s book, which includes a reflective autobiographical essay by the author, or consider enrolling in the online seminar series starting on 24 January 2026: Jung, Dante, and the Making of the Red Book: The Fire Seminars.

References

Tommaso Priviero, PhD

Tommaso Priviero, PhD

Tommaso Priviero is an analytical psychologist and historian of psychology based in London. He received his PhD from University College London (UCL) and currently holds a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL).

His book Of Fire and Form: Jung, Dante, and the Making of the Red Book (Routledge, 2023; with a preface by Sonu Shamdasani) received the prestigious 2025 “Eugenio Montale Fuori di Casa” award.

He is a registered member of the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP), the British Psychoanalytic Council (BPC) and the International Association for Analytical Psychology (IAAP).

Learn more

- Dante and love in C.G. Jung’s Red Book—an article by Tommaso Priviero

- Jung, Dante, and the making of the Red Book—a reflective autobiographical essay by Tommaso Priviero