In this illuminating article, Rachel Huber explores the deeper meaning of Christmas beyond its commercial trappings. Drawing on archetypal symbolism, she examines how the holiday invites us to engage with light and shadow within the psyche, the interplay of cyclical and linear time, and the transformative power of love.

From the hidden dimensions of the Self to the archetypal roles of Mary and Joseph, the author guides readers through a rich journey of inner reflection and spiritual renewal, revealing how Christmas can serve as a catalyst for personal and collective transformation.

French version of this article

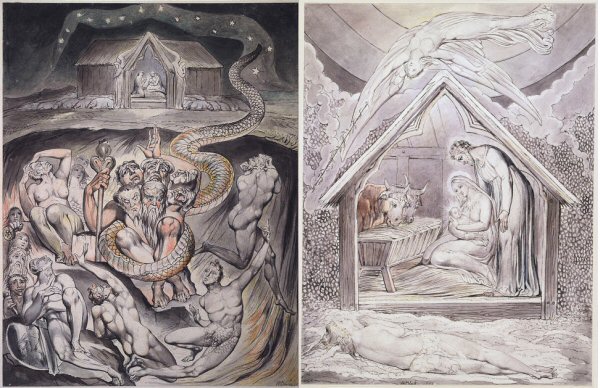

Watercolor Illustrations to Milton’s “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” by William Blake

On this page

- No! Christmas is not just a commercial holiday!

- Subjective experience of the psyche: coexistence of cyclical and linear time

- Jung’s complementary views of time

- Christmas and Shadow: light emerging from darkness

- Joseph: the unrecognized role of the Shadow in the Nativity

- A concrete example of Shadow projection at Christmas

- Emergence of the Self: an experiential discovery

- Christmas and its plural loves

- Mary in the Nativity: the reconciling feminine guiding the reintegration of Eros

- Christmas beyond appearances

No! Christmas is not just a commercial holiday!

Although it cannot truly be called universal, this celebration has become a global cultural phenomenon, drawing people together around fundamental values such as sharing, joy, warmth, and love, while also responding to our innate need for connection and transcendence.

Beyond the superficial festivities, the traditions, rituals, and symbols specific to the season reveal the impact of universal archetypes on our inner life.

According to Carl Gustav Jung, light, the central symbol of Christmas, reflects the emergence of the Self, a fundamental archetype that brings the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the individual into harmony. This encounter takes place at the heart of darkness, reminding us that inner transformation is often born of obscurity and chaos.

Subjective experience of the psyche: coexistence of cyclical and linear time

Thus, in this interplay of light and shadow, where the Self reveals itself through the journey from turmoil to harmony, we encounter an essential dimension of our inner experience: time. Christmas, in its symbolism, invites us to consider how time, both cyclical and linear, shapes our psyche, revealing modes of existence that intertwine and transform as our inner life unfolds.

The concept of cyclical time has its roots in ancient societies, particularly in mythological, religious, and agricultural traditions. These cultures understood time as the perpetual repetition of natural cycles, such as sunrise and sunset, the seasons, or the phases of the moon. Cyclical time embodies the eternal return, a structure in which every ending heralds a new beginning.

This conception is found in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, Indian, and Native American cultures. In these traditions, the cycle was associated with regeneration, rebirth, and sacredness. Agricultural rites celebrated the passing and renewal of the harvest. In Greek mythology, for example, Dionysus embodied this cyclicity through his death and resurrection, while major Eastern traditions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, regarded time as a succession of eras or karmic rebirths. Cyclical time is also deeply connected to religious rites and festivals, including Rosh Hashanah, Easter, Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, and Christmas.

The linear conception of time, with a beginning, middle, and end, is associated in particular with major monotheistic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These religions present sacred history that unfolds in a linear manner, with an initial creation, a narrative marked by significant events, and an eschatological end. This perspective introduces an absolute origin in the Creation and an ultimate end in the Last Judgment or Revelation.

While monotheistic religions have given momentum to the linear conception of time, we must not overlook the contributions of philosophy, which have explored concepts of duration, eternity, and becoming, nor those of the sciences, which have proposed increasingly precise models of time. This transformation reflects an evolution in the way of conceiving the world and humanity’s place within it. Linear time invites moral, historical, and individual progression.

Jung’s complementary views of time

Despite this evolution, the cyclical view of time does not disappear entirely. Religious festivals such as Christmas, which return each year, retain a cyclical imprint while remaining part of a linear framework. Likewise, certain pagan and modern traditions, such as the New Year celebrations or birthdays, continue the notion of periodic renewal.

Jung offers an interpretation of this duality: he sees cyclical time as an archetypal representation of the rhythms of the psyche. The repetition of life cycles—birth, death, and rebirth—is essential to inner transformation. Linear time, by contrast, embodies progress toward the unique and personal process of individuation.

These two views do not oppose each other but complement one another, providing humanity with a temporal framework that links the myths of the collective unconscious to the personal and unique experience of the individual quest.

Christmas and Shadow: light emerging from darkness

Christmas is celebrated at the time of the winter solstice, the day when night is longest and day shortest in the Northern Hemisphere. For our ancestors, it was a pivotal moment, marking the lowest point of the solar cycle. They feared the sun might die and darkness reign forever. Yet the winter solstice is also a moment of hope. Immediately afterwards, the days begin to lengthen, signaling the return of light and the renewal of life.

In Jungian thought, the Shadow represents the repressed, ignored, or denied aspects of the psyche that dwell in the unconscious. Progress along the path of individuation requires confronting what lies hidden in the dark folds of our inner world. Christmas, as a moment of rebirth, can be seen as an encounter with this Shadow: it is in the crucible of darkness that inner light emerges, often linked to the awakening of the Self.

But what is Shadow? Here is Jung’s definition:

By shadow I mean the negative side of the personality, the sum of all those unpleasant qualities we like to hide, together with the insufficiently developed functions and the contents of the personal unconscious. (Jung, CW7, note 5)

Although we do see the shadow in a person of the opposite sex, we are usually much less annoyed by it and can more easily pardon it. (Jung, Man and his Symbols, p. 169)

In this definition, Shadow appears as that part of ourselves we consider unflattering, the part we prefer to hide, not only from the eyes of others and society, but also from our own view. Yet the notion of Shadow is far broader:

He clarifies:

But the shadow is merely somewhat inferior, primitive, unadapted, and awkward; not wholly bad. It even contains childish or primitive qualities which would in a way vitalize and embellish human existence, but—convention forbids! (Jung, CW11, para. 134)

Jungian analyst Élie Georges Humbert, who was one of the founding members of the Société Française de Psychologie Analytique (SFPA), provides the context:

In analytical psychology, concepts are not abstractions; that is, they are not formed to designate entities, nor to denote factors or forces within the psyche. Jung arrived at the notion of the shadow through the work of interpreting dreams. The shadow is, first and foremost, a category for the interpretation of dreams. In dreams, various figures appear that are of the same sex as the dreamer, forming the manifest content of the dream. These figures stand in relations of opposition, accompaniment, or friendship to the dreamer. How are these figures to be understood? And to what do they correspond?

For Jung, these figures represent, on the one hand, a certain position of the dreamer’s psyche: a position that is sexually differentiated in the same way as consciousness and thus stands in a relationship that could be described as analogous to consciousness. This contrasts with figures that are feminine in a man’s dreams, or masculine in a woman’s dreams, which indicate not positions of the psyche parallel or analogous to consciousness, but complementary positions, aligned with it, and thus figures that function as mediators toward the unconscious. In a very general sense, this is how Jung defines the anima and the animus: as mediating functions.

If we now identify, in dreams, figures of the same sex as the dreamer, this is not a matter of mediation. These would be parts of the psyche that could enter the field of consciousness, already in a position similar to that of consciousness, but that, in fact, still express themselves only in dreams and still appear only in dreams.

These notions are not concepts that isolate or generalize elements, but rather categories that make interpretation possible. And not an intellectual interpretation, but ones that enable the waking consciousness to relate to what has appeared in the dream. [translated from Jung ou la totalité de l’Homme futur “anima et animus” 2/8]

Jolande Jacobi adds:

I can control only what I am conscious of, which is why, first of all, one must work on one’s shadow in the process of individuation. That is, the repressed and hidden traits that one does not dare to bring into the ego. The traits of the shadow are always of the same sex as the ego; they are phenotypically of the same sex as the ego. After this comes the development of the other side of the personality: for a man, the feminine aspects; for a woman, the masculine aspects.

And according to Jung, and this is very important for him, [this other side] should only be worked on after the shadow has been integrated into the ego. Because the ego is too weak to encounter the opposite sex without this expansion through the traits of the shadow. For this reason, Jung strongly recommended that in the first part of life, one should focus, in preparation for the process of individuation, on expanding the ego through the shadow. When one encounters the anima and the animus, the second part of life has opened its door, and this second part depends on the length of one’s life. [translated from Jung ou la totalité de l’Homme futur “anima et animus” 2/8]

It is important to note that the Shadow does not manifest in a single form. As Élie Humbert explains, it can appear internally, for example through dreams.

Joseph: the unrecognized role of the Shadow in the Nativity

Archetypically, Joseph, often cast as a secondary figure, embodies a part of the Shadow in the Nativity narrative. Faced with existential doubt at Mary’s announcement, he experiences universal anxieties tied to the unknown, judgment, and feelings of inadequacy. His social position leaves him in solitude, exposing him to fear of exclusion and a deep need of belonging. The immense responsibility of raising the child Jesus confronts him with profound uncertainties, including fear of failure and insecurity.

By exploring these shadowed facets of Joseph, we gain a deeper understanding of how the Shadow is integrated into the narrative. His journey, marked by the gradual acceptance of doubts and fears, reflects a profound inner transformation. Far from a static figure, Joseph’s inner evolution serves as a model, inviting us to recognize and embrace our own Shadow on the path toward greater wholeness.

The Shadow can also appear externally, particularly when a person projects onto someone else traits or characteristics concealed within their own unconscious.

A concrete example of Shadow projection at Christmas

The Shadow often emerges in the family tensions that surface during this period. Heightened by the idealized expectations surrounding Christmas, these tensions can reveal projections: repressed grudges, unspoken judgments, or fears cast onto certain family members.

Deborah, 26, comes to the clinic for the first time in early September, struggling with emotional stress stemming from her relationship with her boss, to whom she cannot say no. In late November, she experiences a panic attack at work. She links a conflict with her boss to recurring disputes with her mother, Helen. Deborah accuses her mother of being selfish and distant, feeling that her emotional needs are never adequately considered.

As the holiday season approaches, Deborah laments “having to take part in this great family masquerade where no one is happy to see each other and everyone pretends to be the happiest”, particularly her mother. This situation stirs a deep sense of frustration, which she seeks to understand and soothe.

Over the course of her sessions, Deborah begins to explore these two relationships more deeply. She becomes aware that her criticism of her mother masks a part of herself she has long refused to acknowledge: her difficulty in expressing emotions and her need for attention. She realizes that she has expected emotional closeness from both her mother and her boss, but above all, that she has never allowed her mother to approach her intimately. This moment of insight marks a turning point in her psychotherapy. Deborah discovers that she has been projecting onto her mother and her boss a part of herself: the fear of vulnerability and her unexpressed need for attention.

Through this exploration, Deborah has begun a process of integrating her Shadow, learning to recognize her own emotional needs and to express them more openly, both to her mother and at work.

Projections of the Shadow play a crucial role, as they provide an opportunity to become aware of aspects of ourselves that we otherwise fail to acknowledge.

Emergence of the Self: an experiential discovery

Similarly, when we come to recognize these projections of the Shadow within ourselves, a path opens: the path of acceptance. This inner movement lays the groundwork for a new insight, much like the birth of Christ in a humble manger in the depth of night. Through the birth of Jesus, Christmas becomes a symbol of the emergence of a new consciousness in the world.

There is a striking parallel with the discovery of the Self. The reunification of the ego, after passing through profound disorganization, resembles the emergence of a new inner center. This process of recentration, as described by Jung, marks a profound transformation in the quest for psychic unity: a kind of inner rebirth that mirrors the process of individuation.

The period from 1912 to 1918 was a time of deep introspection for Jung, marked by a depressive episode. His break with Freud brought him face to face with a psychological decompensation.

It was during Advent of the year 1913—December 12, to be exact—that I resolved upon the decisive step. I was sitting at my desk once more, thinking over my fears. Then I let myself drop. (Jung, MDR, p. 179)

By facing and engaging with the contents of his unconscious during this crucial period of his life, Jung developed the notion of the Self. This concept reflects both his analytical theory and the deeper meaning of human existence.

Gerhard Adler illuminates the relationship between the divine in Jung’s work and the concept of the Self:

This is where the link lies between religious symbols and Jung’s contribution to modern religion and to the problems of modern man in his relationship with religion. Many people express strong criticism of traditional religious values, but it seems to me, at the same time, that among them, many are attempting to rediscover new personal values.

Jung once said that modern man needs something more than faith, love, and hope. The fourth element that must be added is experience. Modern man needs to experience before believing, before he can embrace any religious value offered to him. It is on this that the current crisis of traditional religion rests, and at the same time, it is the basis for the hope of a new, authentic religion that will spring from human experience and from the pursuit of personal independence.

Jung approached this in the following way: for him, the Self is the Archetype of God. And here we must avoid a serious misunderstanding that has greatly harmed a proper understanding of Jungian thought: Jung does not say that the Self is God, but simply that the Self is the Archetype of God. In other words, it is an unconscious idea, an unconscious image of the psyche, which is broader than the ego. Jung spoke of the inner God: the Self is the expression of this inner God that man seeks to discover, and must encounter before he is capable of believing. [translated from Jung ou la totalité de l’Homme futur “Le Symbole du soi et individuation” 3/8]

The Self, the expression of the inner divine within each person, serves as a guide in the search for harmony between the conscious and the unconscious, and in the pursuit of psychic and spiritual unity. Through this process, a fundamental energy unfolds: love, which becomes a force of reconciliation between the individual and the universal, between the earthly and the divine.

Love, as transformative power, also plays a central role in this quest for harmony. It functions not only as a mediator between the individual and the universal, between the physical world and the sacred, but also as a catalyst in the process of individuation.

It is within this movement that love may be understood in relation to what Jung calls the transcendent function. By uniting opposites—conscious and unconscious, light and shadow, Eros and Logos—this function allows for psychic transformation and the emergence of a new inner wholeness. In essence, love is not simply an emotion or a feeling, but a psychic energy that fosters the union of opposing polarities, serving as a bridge toward the integration and fullness of the Self.

Christmas and its plural loves

This can be linked to the continuity of the individuation process. As Jolande Jacobi emphasizes, the second half of life offers a particularly favorable period for exploring and integrating the relationship with the anima or animus.

In Jung’s experience, the anima plays an essential role as a mediator between the unconscious and the conscious. He observes that it manifests through various figures, initially projected onto people or external images, reflecting the unconscious aspects of the individual’s psyche.

As Marie-Louise von Franz notes, these projections of anima figures evolve over the course of the individuation process:

But after all, a woman represents a multitude of possibilities! At the lowest level, we could place, for example, the “pin-up girl”, whose role seems to be merely to excite biological functions. Next, a certain spiritualization of the woman can appear with the Virgin Mary, who is also a projection of a highly evolved psychic femininity within a man, and then Minerva, representing wisdom… So, what exactly is this hierarchy of the anima? When a man knows little of his anima, it begins with erotic fantasy. As his relationship with the anima evolves, he develops a connection in which his relationship with women becomes humanized. Next comes the idea of spiritualization, as in the mysticism of the Middle Ages, where the Virgin was chosen as a symbol of the anima, so that it would no longer be projected onto a real woman. But this was truly a differentiation of Eros internally.

Wisdom, about which Jung said with a smile, “less is more,” meaning that there is a descent back into matter, into the concrete, into the more human.

For Jung, a man who has developed all his relationships with the anima could truly have a relationship with a woman and would really understand women. Not just on a biological level, but on the level of the human being. He could make a complete assessment, but more importantly, he would have a sentimental attitude of wisdom toward himself and the world, toward the unconscious and the external world. [translated from Jung ou la totalité de l’Homme futur “anima et animus” 2/8]

These anima figures reflect the stages of inner evolution. Exploring the dimension of the opposite sex within oneself brings forth deep and sometimes concealed aspects of the soul. This paves the way for a more authentic encounter with oneself. By accessing a fuller image of the soul, we cultivate a more balanced relationship with our emotions and affects.

It involves connecting with a broader dimension of love, which, in this context, is not confined to a mere individual emotional experience, but manifests as a universal principle, unfolding through diverse forms and expressions across human life.

The encounter with this dimension marks a major turning point, symbolizing the end of a phase in which love was primarily directed toward biological fulfillment. From this point onwards, love turns toward an inner quest, revealing a “beyond that is emerging,” a more spiritual and introspective dimension of existence.

Mary in the Nativity: the reconciling feminine guiding the reintegration of Eros

In Christian symbolism, Christmas is marked by the figure of Mary, mother of Jesus, who holds a central place as a figure of unconditional love, mediation, and intercession. In analytical psychology, the Virgin Mary is seen as a projection of the anima, which, as Marie-Louise von Franz emphasizes, represents a highly developed aspect of psychical femininity in men. Von Franz points to medieval mysticism, a spiritual and theological movement that influenced Christian theology and practice by offering a more personal, interior space for the expression of faith. In this context, Mary became an idealized and one-sided projection of the male anima, embodying a spiritualized, luminous, and disembodied feminine.

Over the course of history, the doctrines of the Catholic Church were gradually developed through the ecumenical councils and the Church Fathers, within the framework of the Magisterium, the teaching authority of the Church from which women were excluded. This process fixed a partial and immaterial vision of the feminine, omitting its aspects related to the Shadow, sacred sexuality, and transformative power.

This projection, while ostensibly intended to differentiate and sublimate aspects of Eros, actually reflects an inability to fully integrate the feminine in its entirety, including its ambivalent and shadowy dimensions.

Such excessive idealization, though aimed at elevating the feminine, exposes an immature and incomplete psychical femininity within the male psyche.

It distances men not only from the integration of the Shadow in the masculine psyche, but also from a genuine humanization of the sacred feminine. By calling for a “descent into the concrete”, Jung critiques this separation of the feminine from matter and lived humanity, advocating for an embodiment that harmonizes these two poles: spirituality and rootedness in everyday life.

But what about women? Mary embodies several powerful archetypes: the Virgin, the Mother, and the Wise Woman, representing purity, compassion, receptivity, nurturing and protective qualities, as well as an intuitive, inner knowledge connected to the feminine. This feminine is not simply a gender attribute, but an archetypal force present within every individual, whether male or female.

French writer Annick de Souzenelle, also recognized for her deep exploration of Jungian psychology, develops in Le Féminin de l’Être [The Feminine of Being] this symbolic and spiritual dimension of the feminine, placing it at the heart of the quest for being. Drawing on the Hebrew translation of the biblical text, she revisits the myth of Eve “taken from Adam’s rib” to reveal Isha. In Genesis, Isha, which in Hebrew means “the woman”, is created from Ish, the man. De Souzenelle interprets the term Isha as representing the feminine of being, as it embodies the inner, receptive, and hidden dimension of the human self: that which has not yet fully come into consciousness. Isha thus emerges as a universal archetype of the feminine in every human being. For de Souzenelle, this dynamic symbolizes not inferiority, but an essential connection with the inner world.

That which is not yet illuminated by the light of consciousness, such as Isha, evokes fear because it represents the unknown, is difficult to control, and carries inherent ambivalence. This aspect of the self, while holding creative and liberating potential, can be projected negatively, as it signals a rupture with the familiar and an invitation to demanding inner work. It calls for confronting repressed truths and questioning established reference points, especially those imposed by the ego or patriarchal frameworks. By requiring a process of transformation, this part of the self, though creative, elicits resistance and anxiety, as it involves facing one’s Shadow and undergoing profound inner reorganization.

And Christmas, with Mary as the central figure, invites us to reconnect with her archetypal vibrations and to achieve a deeper integration of all aspects of this polarity within our psyche, thereby allowing the Self to be welcomed in each of us. This journey toward the “feminine of being” constitutes a fundamental stage in spiritual development and inner transformation, aligning with the dynamics of the individuation process described by Jung.

Jung wrote:

The woman is increasingly aware that love alone can give her her full stature, just as the man begins to discern that spirit alone can endow his life with its highest meaning. Fundamentally, therefore, both seek a psychic relation one to the other; because love nee’s the spirit, and the spirit, love, for their fulfilment. (Jung, Contributions to Analytical Psychology, p. 185)

In this way, love helps us move beyond the one-sided attitudes of the ego. This evolutionary dynamic highlights that, when the major archetypes of the collective unconscious associated with the Nativity are activated, and in resonance with our own psychic structures, we are invited to embark on or continue a true inner alchemical process.

Christmas beyond appearances

In its symbolic depth, Christmas leads us far beyond mere appearances. This suspended time becomes a privileged moment in which shadow and light, often in tension within us, find a space for dialogue, encouraging us to recognize and integrate the opposing polarities that dwell within. This journey casts light on our shadows, both internal and projected, and invites a reconnection with the unity of our being.

Finally, like the Self, which embodies the archetype of God, Christmas invites us to awaken this divine light within. The birth of the child Jesus in the humble manger, in the depth of the night, testifies to this revelation of the inner divine.

The reconciling feminine, embodied in Mary, highlights our innate capacity to welcome the divine into the material world.

This transcendent function of love opens the path to the Self, encouraging us to discover or rediscover our own sacred dimension. Through this process of incarnation, Christmas becomes a privileged moment in which humanity and the divine can be bridged, allowing us to embrace the “inner God” and draw closer to the profound reality of the Self, opening ourselves to all dimensions of love.

Dear readers, I wish you a deep and mindful presence with yourselves during this Christmas season.

Original article by Rachel Huber,

translation by Peggy Vermeesch.

December 2025

Rachel Huber

Rachel Huber is a psychopractitioner, sophrologist, teacher, trainer, and superviser in the southeastern region of France. She is accredited by the French Federation of Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis (FF2P).

Deeply committed to Jungian psychology and drawing on foundational texts, she illustrates how this approach sheds light on the questions and challenges we face in our modern ways of life.

For more information, visit her website: Cabinet Sophro-Psy

Articles

- Christmas, Shadow, and the reconciling Feminine as pathways to the Self

- Visit of the house of Emma and C.G. Jung

For a list of articles and interviews published in French, visit Rachel Huber’s page on EFJ.