In this diptych, Dragana Favre explores the Backrooms as a contemporary figure of katabasis, a descent into the collective unconscious in the digital age. Between disintegrated mythology, the anxiety of emptiness, and liminal aesthetics, she brings video games, cinema, and contemporary art into resonance with Jungian thought.

This article presents an original reflection illuminating new forms of imagination and psychic dissociation in our data-saturated world.

French version of this article

On this page

- Liminal horror, digital katabasis, and psychic dissociation

- The Backrooms: An emerging digital myth

- A myth without gods: Wandering as contemporary katabasis

- What do we mean by katabasis?

- The Backrooms as a reenacted katabasis

- Game levels: Urgencies without cause, oppressions without threat

- From myth to empty repetition: A post-symbolic landscape

- Dissociation and non-place: The unconscious without transcendence

- Enduring absence, relearning to dream

- Cinema, art, and threshold spaces in the contemporary psyche

- Bibliography

Liminal horror, digital katabasis, and psychic dissociation

Where understanding fails, images appear.

What is repressed becomes perceptible in a half-light, as a spectral image, and it is thus encountered as uncanny. (Jung, CW9i, para. 66)

The Backrooms: An emerging digital myth

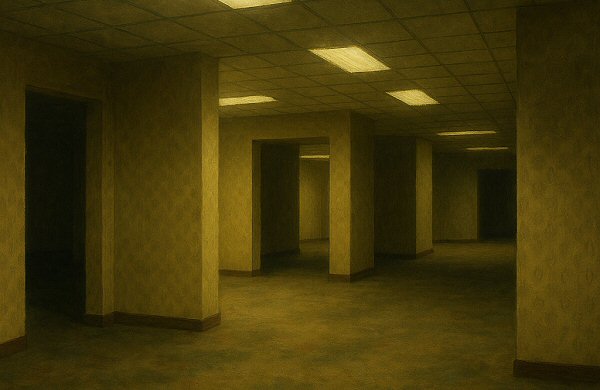

In recent years, a strange place has crept into the margins of the digital imagination: the Backrooms. It is neither a simple urban legend nor a fleeting meme, but an emergent myth, born anonymously on an online forum and spreading virally, like a symbolic contagion, across video games, interactive stories, YouTube videos, and haunted TikToks.

A myth without heroes, gods, or coherent narrative, yet with a mental architecture of growing density. An empty space, yet saturated. Silent, yet rumbling with presence. A no man’s land carpeted with damp floor tiles, bathed in sickly yellow light, and populated by endless corridors with no outside, no exit.

In this cartography of metaphysical boredom, one does not die, one wanders.

And that wandering is anything but trivial: it mirrors, pixel by pixel, a descent into the unconscious.

But here, the descent does not fall.

It stretches.

It dilates within a borderless, directionless, endless time.

This is not the hell of motion or torture, but the nightmare of a frozen present, an eternal return without variation, a slow, circular temporality in which every second weighs like an eternity without escape.

Something is lurking, but never comes. Or rather: it is time itself that lurks.

What watches is this invisible loop, this faceless vigilance where waiting becomes substance, silence thickens, and anxiety turns to atmosphere.

It is not the threat of an event. It is the crushing of a future that never arrives, the vertigo of an evacuated tomorrow.

You no longer know how long you’ve been there.

Perhaps forever. Perhaps never.

A myth without gods: Wandering as contemporary katabasis

The Backrooms do not simply show the fear of emptiness. They reveal the emptiness of fear.

They belong not to fictional imagination but to a raw symbolic space; a one-way mirror held up to a saturated psyche. Almost nothing happens there, yet everything insists: an atmosphere, a climate, a presence that never quite appears but whose insistence wears down reality, like water dripping on stone.

What do we mean by katabasis?

In Jungian and depth psychology, katabasis designates a symbolic descent into the unconscious. It is often experienced as a crisis, a dark night in which the structures of the ego collapse and the material of the Shadow surfaces, opening the way for transformation.

It corresponds to what mysticism calls the “dark night of the soul,” and in alchemy, the nigredo: the blackening phase preceding all rebirth. In the process of individuation, katabasis is a necessary step: a plunge into the unknown psyche to recover the lost or repressed aspects of the Self.

The Backrooms as a reenacted katabasis

This environment reenacts, in contemporary and degraded form, the motifs of katabasis—the initiatory descent into the depths of the psyche:

- Loss of orientation: The space is not linear but cyclical, distorted, uncertain. The lights flicker with no apparent logic, in an organic rhythm, as if the architecture itself were breathing, or suffocating.

- Progressive dehumanization: In Backrooms 1998, the camera trembles, breath quickens, and sounds take on life. The player no longer directs the experience; they are absorbed into it, trapped in a loop where time doesn’t pass; it folds in on itself.

- Encounter with the unnamable: Blurred entities, faceless, without clear intent. They do not always pursue; sometimes they only watch. And that gaze, without origin, without judgment, is more unsettling than an attack: it is the naked face of anxiety.

Game levels: Urgencies without cause, oppressions without threat

Certain game levels embody these variations. In Level !, nicknamed Run for your life!, the player is thrown into a panic-stricken flight without reason or destination. Urgency precedes narrative. Conversely, Level 0 stages oppression without threat: no visible enemy, yet a constant tension—as if mere existence there constituted an assault on psychic integrity.

In these worlds, dissociation is not a consequence; it is the very structure of space.

From myth to empty repetition: A post-symbolic landscape

This dissolution of narrative markers—no quest, no monster, no salvation—renders the Backrooms profoundly post-mythological. Myth no longer structures experience; it collapses into empty repetition. The sacred is no longer invoked; it is simulated. We no longer pray to gods; we explore levels. We no longer consult oracles; we decrypt data dumps.

The Shadow, in Jungian psychology, often emerges at the margins—in dreams, slips, and liminal states. Here, it manifests in the hyperrealism of a flickering neon, in textures too perfect, in corridors endlessly repeating. It no longer rises from a dark forest, but from the sterile flicker of a world that refuses to end.

Dissociation and non-place: The unconscious without transcendence

As in certain clinical dreams, a thousand-story house, an empty hospital, staircases leading nowhere, the Backrooms replay a fundamental anxiety: that the world might be full yet meaningless, saturated with detail yet devoid of significance.

In our culture overloaded with data, alerts, and functional rationality, these spaces appear as an inverted outlet: a place where nothing happens, yet everything weighs. The stained carpet, crumpled paper, hums without source, all signs that no longer signify. The sign has detached from meaning.

Marc Augé called such spaces non-places: airports, hotels, shopping malls—transit zones without identity. But here, the non-place becomes a total place, a closed scene where the subject loops endlessly within an environment that denies the symbolic.

Jung’s transcendent function cannot operate; no third way emerges. Only the return of the same remains.

Enduring absence, relearning to dream

The space of the Backrooms is not merely a dystopian architecture. It is a fractured mirror in which the contemporary psyche explores its own vertigo. Between sensory saturation and symbolic absence, these spaces reveal a deep threshold, where archetypal forms no longer manifest through mythology but through the structure of emptiness itself.

In this frozen wandering, the goal is not to interpret but to endure absence, and perhaps, by inhabiting it, to relearn how to dream otherwise.

Cinema, art, and threshold spaces in the contemporary psyche

At first glance, the Backrooms seem unique, almost aberrant. Yet they belong to a broader constellation—a contemporary sensibility marked by spatial anxiety, the dissolution of identity, and the haunting persistence of an inerasable void.

For decades, artists, filmmakers, and game designers have been crafting analogous worlds: liminal, ambiguous spaces in which imagination no longer unfolds as narrative but decomposes into state. These are not universes of story but worlds of intensity, where the psyche no longer seeks salvation but an exit; sometimes without escape.

Certain films embody this aesthetic with disturbing acuity.

In Beau Is Afraid (Ari Aster, 2023), every place becomes a somatic ordeal: the overprotected apartment already saturated with anxiety and paranoid control; the street an urban nightmare; the forest a hallucinatory womb; the home a reversed maternal matrix. These are not settings but psychic chambers, sites of absorption.

In Synecdoche, New York (Charlie Kaufman, 2008), it is the stage itself that devours life. A man rebuilds his city inside a warehouse to endlessly reenact his own existence. Copies proliferate, doubles overtake originals, the story coils in on itself until saturation: theater becomes psyche, and psyche, empty repetition.

With Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), space becomes a mysterious answer: the Zone says nothing, but it judges. It waits. It murmurs. With every step, something invisible decides—as if space contained latent judgment. Slowness here is not aesthetic but metaphysical: it generates suspended tension, an unnameable threshold.

In a more brutal register, Cube (Vincenzo Natali, 1997) stages a geometric trap where characters wander from room to room without grasping the logic that confines them. The human has no story left—only reflexes. Each gesture is survival within a cold, mathematical, disembodied system.

In The Platform (Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia, 2019), descent is reduced to a pure vertical axis. A platform carries food cell by cell; the lower one goes, the more hunger, shame, and violence supplant language. It is not only the body that starves, but subjectivity itself, deprived of transcendence.

In all these films, space is not backdrop but symptom. What terrifies is not the decor but what it prevents from emerging. Every room, corner, and threshold is a closed stage where symbolization fails. It is no longer about depicting hell, but constructing it, layer by layer, until it becomes breathable.

This movement of absorption extends into contemporary visual art, where it is no longer the figure that speaks but the void.

In Gregor Schneider’s installations, such as Haus u R, rooms seem ordinary, yet something is off: corridors repeat identically, walls imperceptibly close in, the air grows dense. One believes oneself at home, yet home is a trap, a soft snare that observes, waits, and dissolves you.

Conversely, Rachel Whiteread solidifies absence. By casting negative volumes, the inside of a room, the imprint of a staircase, she gives form to what is no longer there. In Ghost (1990) and House (1993), absence becomes monument, mourning becomes structure, disappearance becomes texture.

With James Turrell, the Ganzfeld Rooms erase contours altogether. Light becomes matter. It floods everything. The eye can no longer anchor itself. There is no depth, no direction, only perception without object. It is no longer we who look: it is the light that looks at us. We float within a borderless threshold.

Even in digital margins, this aesthetic proliferates. On Reddit, Tumblr, or TikTok, young creators post images of overly empty corridors, deserted parking lots, or abandoned swimming pools with blurred reflections. Ordinary scenes ripped from context: the familiar turns spectral, the banal dissociative. These images show nothing, yet evoke a nostalgia without object, a loss without narrative, a diffuse unease.

As in the Backrooms, everything could be a sign, but none opens. Symbolization is suspended—as in dreams where one revisits a familiar house, but everything is frozen, too clean, too precise. The space is recognizable, yet it no longer recognizes you. The eye searches for meaning, but finds only surface. Nothing answers.

What the Backrooms, liminal cinema, games, and contemporary art share is neither a genre nor a language; it is an experience of threshold: a suspension, a dense formlessness, an intensity that seeks not to be told but to be felt.

They all speak of the same void. the one that the symbolic can no longer inhabit but that nevertheless persists: an anxiety without origin, a presence without figure, a call without voice.

Jung wrote that the unconscious never ceases to produce images, even when the ego collapses. Yet sometimes, it is the images themselves that waver, too sharp, too empty, too repeated, or conversely, too blurred, too unstable, too dissolved. It is no longer imagination that gives form to chaos, but chaos that contaminates imagination.

Perhaps, then, one must create without it, forge thresholds where narrative no longer exists, welcome formlessness as the last form of presence. And in this suspension, not flee, but wait for something still to insist.

These liminal spaces, between wandering and absence, invite us to question what imagination becomes in our saturated world.

At the end of this exploration, perhaps what remains is to inhabit the void, so as to relearn how to dream.

Thus emerges a contemporary mirror of the psyche: fragmented, uncanny, yet still bearing the possibility of transformation.

Original Article & translation by Dragana Favre.

November 2025

Bibliography

Dragana Favre, MD, PhD

Dragana Favre is a Swiss psychiatrist (FMH) and neuroscientist specialized in analytical psychotherapy. Trained at the University Hospitals of Geneva and the Antenna Romande of the C.G. Jung Institute in Küsnacht, she maintains a private practice in Geneva and lectures internationally on Jungian psychology, consciousness, and symbolization.

Dragana Favre is a Swiss psychiatrist (FMH) and neuroscientist specialized in analytical psychotherapy. Trained at the University Hospitals of Geneva and the Antenna Romande of the C.G. Jung Institute in Küsnacht, she maintains a private practice in Geneva and lectures internationally on Jungian psychology, consciousness, and symbolization.

She holds a PhD in neuroscience from the University of Alicante and a Master’s degree from Göttingen, and develops an integrative approach grounded in archetypal dynamics, psychic temporality, and the phenomenology of consciousness.

She serves on the board of the International Association for Jungian Studies (IAJS), co-chaired the annual IAJS conferences in 2024 and 2025, and hosts the Jungian Salon, a living forum at the crossroads of clinical practice and contemporary thought.

Personal website: www.draganafavre.ch.

Articles

- Wandering in the Backrooms: Liminal spaces, digital myth, and a Jungian reading of the Void

- Falling in love with life

Learn more

- From neuroscience to the depths of the psyche—an interview with Dragana Favre, conducted by Jean-Pierre Robert