In a thought-provoking conversation, Peggy Vermeesch joins Jungian analyst Martin Schmidt, whose work spans the symbolic, aesthetic, and clinical. Drawing on Jungian and psychoanalytic thought, Schmidt reflects on the concept of the Self, his work with psychotic patients, cultural complexes in Russia and China, the role of beauty, art, and the sublime, temporality, the breaking of the analytic frame, and eroticized trauma.

The interview delves into the paradoxes of analytic work and the risks and sacrifices inherent in the process of individuation.

Video interview in English | Text in French

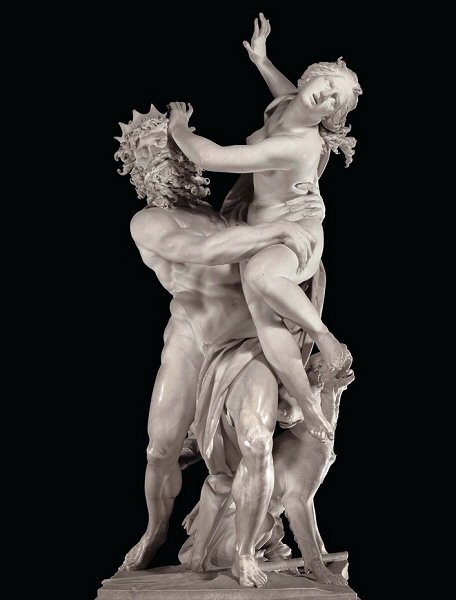

The Rape of Proserpina by Bernini (CC BY-SA 3.0).

On this page

- Individuation and the concept of the Self

- Jungian analytic work

- Cultural complexes

- Risk and sacrifice

- States of grace in analysis

- The dark side of the Self

- Beauty, ugliness and the sublime

- The importance of paradox

- Temporality, and breaking of the frame

- Eros and eroticized trauma

- Freud’s cancer

- The Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP) in London

- Analytic training

Individuation and the concept of the Self

Peggy Vermeesch: The concept of the Self runs through much of your work, for example in a book published last year called Contemporary voices on Individuation, edited by Giorgio Tricarico, in which you wrote a chapter called Individuation: The three main decisions in life require taking risks. You talk about a key difference between Jungian and other psychodynamic traditions. Could you say more about this?

Martin Schmidt: For me, the key difference is in terms of the understanding of the Self. For Freud, the self is not an agency. It’s a term to describe the totality of body and mind, and the main agents or players in the psyche are the ego, superego, and id. For Jung, the most important dynamic is that between the Self and the ego. The ego is part of the Self, but the Self also has agency. It has its own active dynamic.

This really appealed to me, and one of the things I came to realize is that, both clinically and personally, it’s so important to become aware of the relationship between the ego and the Self. It occurred to me that there seem to be three main questions in life that everybody has to address:

- What to do with one’s time.

- Whom to spend that time with.

- Where?

I noticed that with my patients, if they just use their ego to answer these questions, they run into trouble. If you rely only on your ego, it means the job you do is most likely to be the one that’s most well paid, or the one that your family want you to do, or the one that most people do in the town, or the one that your school advises you to do. Your choice of partner is most likely to be the best looking, the richest, or the one your family approves of. Or it can be the one your family really doesn’t approve of, but it’s still coming from the ego. And similarly, concerning where you live, it’s most likely to be in the town you’ve always lived, close to your family and friends, or the nearest big city.

But if you use both your ego and Self to answer those questions, then what you do may not be the best paid, but it will be meaningful to you, maybe even a vocation. It will be fascinating. It will be something that you look forward to doing, that energizes you, that feeds your soul, that you feel is worthwhile. Secondly, your partner may not be the best looking or wealthiest, but there will be a profound connection. It will feel as if “they’re the one”, as if there’s something special between you, that there’s real love. And thirdly, you can live wherever, because your connection to yourself means that you can make a home anywhere.

Freud doesn’t share this idea of a dynamic Self, which has been so formative and important for me.

What led you to become a Jungian analyst?

Like a lot of young people in their 20s, I had an ontological crisis about what life meant and what I should do. I read a lot of spiritual books, like those of Khalil Gibran, Hermann Hesse, Rumi, Lao Tzu, Ouspensky, Gurdjieff, and especially Krishnamurti. And this led me to Jung.

One of the things that stood out was Jung’s position on belief. He said words to the effect: “I don’t believe, I can’t believe. Either there’s a reason to think something, or I can’t believe it. Belief is a conviction about which you have no certain knowledge. If you know, you don’t need to believe.” This really resonated with me.

Later, I discovered he wasn’t just offering me a philosophy, but a possible career, a way of life. I could use this. I’ve never been really interested in money or business, but I’ve always wanted to help people. I was also aware that I have my own narcissistic injuries and defenses that need to be attended to. It seemed to me that training to be a Jungian analyst would give me an opportunity to do something meaningful that could help others as well as myself, and quench my thirst for lifelong learning.

When I first finished my degree in psychology, I sort of blindly went into a government psychology job and did some research, which was okay, but not particularly nourishing. But when I found myself working as a psychologist in a psychiatric rehabilitation center with psychotic patients, I felt I had found my place. It was so exciting, so interesting, to work with people who had had experiences I couldn’t imagine. This led me to train, first as a psychotherapist, and then as a Jungian analyst at the SAP.

Do you think individuation is commonplace or does it require years of analysis? How is the analytic setting different from other relationships in supporting this process?

There’s a big difference between maturation and individuation. Everybody matures. We all crawl, then walk, and then go through adolescence, midlife and old age. But individuation means something else. It means becoming oneself, finding out who you are, developing your personality, taking risks and expanding your perspective.

This can be achieved in many ways. It’s not the case that you need analysis to individuate, but I think it can foster individuation. It’s a bit like growing tomatoes in England. You can grow tomatoes in your garden, but if you grow them in your greenhouse, you usually get better tomatoes. You can more easily control the conditions.

Analysis is like a greenhouse in that sense. Because, in ordinary relationships, there’s a lot of distortion. Parents, partners, friends all have investments in us, which makes it harder for us to be totally honest with them. We don’t want to hurt their feelings. Whereas in analysis, we are privileged to hear the truth, or something close to it. It really encourages authenticity. The way to individuation is to be honest with yourself: facing uncomfortable truths, which I think is much easier to do in analytic relationships than outside.

Such a deep process can take years. It has certainly helped me with my own individuation process, and I can see it helps many of my patients on the same path.

Jungian analytic work

What comes out strongly in all your writing is your great love and respect, and I imagine gratitude, for Jungian analytic work. How have your own years in analysis shaped your individuation?

The key word for me is gratitude, which is a gift from Melanie Klein. She wrote a book called Envy and Gratitude. In it, she came up with a beautiful formula, which I found to be true, which is that the more envious you are, the more unhappy and more mentally ill you are likely to feel. Whereas the more grateful you are (for who you are and what you have), the happier you are and the more well you feel. I think that’s a guiding principle in my own life, but also in my clinical practice.

If you can achieve a state of gratitude, you’re in a good place, because envy not only attacks the object you envy, it also attacks your own good objects. That’s why it’s so pernicious. For example, I had a patient who bought a Ford Mondeo, not a spectacular car, just a Mondeo. But he loved it. It was his first car. He cleaned it every week, turned on the radio, and just drove. For those first few weeks, he thought: “Oh my God, this is wonderful. I love my car. I love my freedom.” Then his brother bought a Mercedes. Suddenly, not only did he hate his brother’s Mercedes, but now his Ford Mondeo became rubbish. He didn’t like it anymore; he was embarrassed by it. He didn’t want to drive it or let his brother see it. This is such a clear example of what Klein is talking about. Envy destroys your own good objects and being grateful is really the road to happiness.

So, yes, of course I’m grateful for my analysis, though perhaps not in the ways you might imagine. I had thirteen years of analysis, four times a week. It was a very intense process. What I’m grateful for is that it wasn’t perfect. In such a long, intimate relationship, you see not only your own shadow and narcissistic injuries, but those of your analyst as well. In some ways, that made it eventually easier to leave, because it wasn’t some idealized process where a guru hands down wisdom. We were really in it together. So, I am very grateful for it. It was formative and played a huge part in my development.

About five years after my Jungian analysis, I also had Kleinian therapy twice a week for a few years, just to get a different taste of what that was like. I was interested, because I had studied a lot of Freud and Klein, as well as Jung. That was a helpful and interesting relationship too.

So yes, analysis has played a huge part in my development and my work.

Do you think it should be recommended that practicing analysts or therapists go back into some kind of therapy or analysis every ten years or so?

Freud recommended five. In his paper Analysis Terminable and Interminable from 1937, he said that no analysis is ever complete. The unconscious is too vast. You can’t possibly solve all your problems. So when you leave analysis you will still be a work in progress. He therefore recommended that one should go back into analysis every five years, which is along the lines of what you’re saying. But this is a bit rich, really, because neither Freud nor Jung had analysis themselves.

I found it valuable to go back into analysis, and if I were to have some kind of crisis or difficulty in the future, I would consider it again, but I wouldn’t say it’s something one should do.

Cultural complexes

I understand that you love to travel and teach in many countries. How did that start and what has it taught you?

I’ve always loved to travel, even before I was a therapist. I love broadening my horizons by experiencing different cultures and meeting different people.

In terms of my work, this probably started about 25 years ago. I was very fortunate to be invited by Jan Wiener to join a small international group of analysts whose goal was to train the first Russian Jungian analysts. This was so exciting. I was so honored to be invited. I felt like a pioneer, going to the Wild East. I loved it. I must have gone three or four times a year for eight years, mainly to Moscow and St. Petersburg. It was fabulous. As a result of the success of this project, I was invited to do the same for four years in Ukraine.

Then I was asked to become the IAAP’s Regional organizer for Central Europe, responsible for coordinating the training of Jungian analysts in eight countries. And in my latest new adventure I have been training the first Jungian analysts in China. I’d say about half my work now is teaching and supervision in different countries, and the other half is analysis with patients.

This endeavor has taught me so much about myself and different cultures. For example, I would be embarrassed to invite any of my Chinese colleagues for lunch in England. In China, you are offered over 20 dishes for lunch! In England, you’re lucky to get a sandwich and a bag of crisps.

I found the cultural complexes fascinating. In Russia, for example, there is the Babushka complex, where grandmothers have disproportionate influence. You see certain constellations in supervision that repeat and reveal these cultural complexes. Nearly half the cases I worked with in Moscow involved men who compensated feeling castrated in families with very powerful mothers and grandmothers by becoming drunk and physically violent.

In China, I noticed two recurring complexes. One is a strong preference for boys, stronger than in any other country I’ve seen, to the extent that some girls are aborted or given away. The other is, of course, the one-child policy. I’ve been teaching in universities where no one in the lecture hall had a sibling. This has a huge impact, especially on the importance placed on academic success. There is enormous pressure on the only child to succeed. Many cases in supervision involve children struggling with the intense expectations of their parents. They study from eight in the morning until ten at night, six days a week, with no time for friendships or play. The parents often bring them to therapy because they have rebelled through self-harm and are refusing to go to school. They are forced to live the unlived life of their parents, which Jung very much warned against.

But the most wonderful lesson is that people are basically the same wherever you go. We are all human beings with the same anxieties and flaws.

Risk and sacrifice

In your 2005 paper Individuation: finding oneself in analysis – taking risks and making sacrifices, you emphasize sacrifice and loss as vital to individuation, and that “the ego has to suffer to allow the Self to express itself”. What kind of sacrifices do you have in mind? And what sacrifices do you think an analyst has to make in the service of their patients?

Ultimately, the main sacrifice in individuation concerns the realization that the ego is not the Self. The ego likes to think it’s in charge. We like to think we’re the big “I am”. The biggest sacrifice is for the ego to realize it is there to be in service of the Self. It’s not there to rule.

There are also narcissistic sacrifices. It’s a relief for many in becoming a parent, because that really lets you know that you’re not the most important creature on the planet. Individuation is about accepting that. The more connected you are with other people, the better you feel.

How that translates into being an analyst is that there’s a lot of sacrifice, not least in realizing people often become dependent on you. So, you have to give them lots of warning about your holidays. You can’t take too long a break. If you have a dependent patient, you need to realize that you might be making a commitment which goes on over 10 years. You’ve got to be prepared for that and manage that responsibility.

Being an analyst also requires an analytic attitude: suppressing your own personality, not disclosing personal details about your family, your life, and your values. It means trying to be authentic, compassionate, but also neutral and dedicated. Real sacrifices are required all the time to practice effectively.

I really like Winnicott’s axiom. He said that to be an analyst, you need to be emotionally present, not retaliate, and not be destroyed. That is excellent advice. We’re often tempted to retaliate when patients attack us, and one of the biggest forms of retaliation can be agreeing to end the therapy. Not being destroyed means maintaining your analytic position. If you become your patient’s friend rather than remaining neutral, you lose that position. We must always try to maintain boundaries and not act out.

States of grace in analysis

In 2017, you wrote a chapter with Catherine Crowther in the book Moments of Meeting, edited by Susan Lord. The chapter is entitled States of grace in analysis. Why did you choose the word grace and what do you mean by it?

We chose the word grace because it captures something about a state of mind where something is received rather than produced.

I’ve been very interested in Jung’s idea that there are two types of thinking. One is directed thinking, generated by the ego, which is necessary for solving problems in a rational way. The other is creative thinking, which comes from the Self rather than the ego. It’s as if we become a conduit, allowing an idea to be received.

I love those moments in analysis when either the patient or the analyst comes up with something, and the other responds: “That’s really interesting, that feels true.” It doesn’t feel as though the idea belongs to anyone. It just emerges or is received.

Bion develops this idea too. He talks about thoughts existing before thinkers, as if there are thoughts waiting for someone to be able to receive them. I love that.

I’ve seen this in both my clinical practice and my own life. You need a certain amount of emotional development, or to have gone through adversity and major life events, to be able to receive a certain thought. For example, there are thoughts that I couldn’t have had before my parents died or before my children were born. I see the same with my patients. Only after certain crises or developments are they able to realize or receive something. The work of analysis is about creating an environment where these states of mind, or states of grace, can occur, allowing truths to emerge that don’t feel as though they’re manufactured by the ego.

Why grace? Because the word grace also has a spiritual transcendent quality. A state of grace is one where you are open to receive something from a higher order. It is not about religion per se, but about being in touch with something transcendent rather than something generated by the ego. There is also grace in physical movement, like in ballet. There is an elegance to this state of mind.

The dark side of the Self

You also write that sometimes the Self is experienced as destructive and leads to “anti-individuation”. How do you understand these contrasting experiences of the Self?

One of the criticisms of Jung is that he’s far too optimistic in his depiction of individuation as an idealized process of self-development heading towards Nirvana. In reality, many of our patients would consider individuation a luxury. They are trying to build up enough ego strength to survive.

Working in psychiatric hospitals, I was shocked by how many patients, especially schizophrenics, have been decimated by tsunamis of psychotic anxiety from the unconscious Self. Their egos have not been strong enough to bear this flood of anxiety, and it has fragmented and destroyed them.

It made me think that the Self is really like a Greek god. It is not just kind and beneficent; it can also be capricious and cruel. The word awe is interesting. Experiences of the Self are numinous, full of awe or wonder. In English, we have a useful play on the word awe: some things can be awe-some, wonderful, but other things are awe-ful, terrible. The experiences of the Self can be both awesome and awful.

For this reason, Jung equated the Self with the God image. The Bible and Greek mythology are full of stories of people who get a glimpse of God and are turned to salt or stone, burnt to a crisp, or shredded by their own dogs, like Actaeon who saw Diana bathing. These stories show that being exposed to the Self is not a light matter.

In 2012, you received the Michael Fordham Prize for your paper Psychic Skin: psychotic defences, borderline process and delusions. Could you tell us a bit about how working with psychotic patients differs from other analytic work?

I was very lucky to work for over twenty years in psychiatric rehabilitation with patients who had schizophrenia and severe personality disorders. Our job was to help them move out of long-term psychiatric hospitals into the community, using diverse methods (individual therapy, group therapy, occupational therapy, art therapy), as well as providing training in practical skills like work, paying bills, and cooking. It was a really exciting time. It also showed me the extremes of the human condition. It’s incredible what someone suffering psychosis goes through, what they endure. It helped me understand the meaning and function of delusions, and how helpful they can be in keeping people alive.

Of course, you have to adapt your practice for psychotic patients. Fortunately, there is a transference to the institution, what Meltzer called the brick mother, as well as to the team. But in one-to-one psychotherapy, adaptations are needed, especially if someone is very paranoid. Shorter sessions can help and, paradoxically, it may help to let the patient be closer to the door rather than you, because they may need to get away. When we started, we had panic alarms in every room, which we got rid of because we knew that would just make the patient more paranoid, as well as the analyst.

I also learned to be careful and not use techniques like amplification or active imagination too much with psychotic patients. They are already lost in the collective unconscious, so the goal is to help them manage their psychotic symptoms. For example, we ran auditory hallucination groups to help patients find a way to interact with their voices. Humor is a vital release for both patient and analyst in these situations.

My time at the Portugal Prints Psychiatric Rehabilitation Centre gave me a strong grounding in diagnosis, assessment, and understanding severe pathologies. It also helped me later, when working with more neurotic patients, to identify their psychotic parts. Some patients are terrified that they are going mad, and I could say: “No, you’re not. I know what going mad and being psychotic is. I’ve seen that. This is not it.”

You’re able to reassure your patient because you’re speaking from real lived authority, real experience. And you’re not afraid of it.

That’s the biggest thing. If you work for 20 years with people who are very disturbed and you’ve seen people breaking down, literally climbing the walls, then you’re not so frightened when someone’s talking about their panic attack or anxiety states.

Beauty, ugliness and the sublime

In your 2019 paper Beauty, ugliness and the sublime you state that the maternal, the feminine, is the source of beauty and aesthetic experience. Could you tell us about the experiment you conducted and what you discovered?

I asked a simple question to over 700 people: “Tell me something beautiful.” I’ve always been interested in the role of beauty and aesthetics in analysis, and I was surprised by the answers. Half of the answers were what I call collective: nature, a landscape, flowers, or a work of art. The other half were more personal, such as “the smell of a cup of coffee”, “my wife’s face”, or “my motorbike”.

A couple of things struck me. Of the 700 answers, probably only about eight would have given a different answer if I had asked 2000 years ago. Motorbikes and coffee did not exist then. The rest were archetypal. You could have asked an ancient Roman or Greek, and they would have given similar answers.

The other thing that really struck me was the gender difference in the personal answers. 86% of men who gave personal answers said the same thing: “a woman” or part of a woman’s body. That’s what they thought was beautiful. Can you guess how many women said “a man” or part of a man’s body?

Ten percent?

Zero. Not one! Instead, 88% of women said the same thing: “a baby” or part of a baby’s body. This supports the work of Mitrani, Winnicott, Bollas, and Meltzer, who all place aesthetic development and the appreciation of beauty with the early experience of mother. Her touch, how she looked, smelled and sounded form this foundation. I think the men, when they said “a woman”, are projecting mother onto women. The women, when they say “a baby”, are identifying with mother.

This is interesting in terms of Jung’s own experiences. His personal mother was very ill and absent, but he talked about his actual mother being mother nature, the mountains, and the reflection of the light on the lake. This was his archetypal mother. He said that for all of us, mother nature becomes the second mother. I think this is why we like to be in nature. It is where we find mother again, after our primary mother.

You write that both beauty and ugliness are essential for a full aesthetic experience, and you describe art as restoring and recreating the loved object, but also involving aggression. Towards the end of your paper, you add this beautiful, perhaps even sublime, sentence: “We see, time and again, how in art beauty renders tolerable the unspeakable horror and shock to which the spectacle of the other exposes us”. Could you unpack that for us?

There’s a quote by Joseph Campbell that I love. He said beauty invokes; it is the mysterium fascinans. The sublime, on the other hand, shatters and overpowers us; it is the mysterium tremendum. Likewise, Civitarese describes the sublime as the aesthetic feeling of being elevated in the presence of something which exceeds the normal parameters of the beautiful, but there’s also something shattering about it. Campbell even says that being in a city that’s being bombed is sublime. Keats notes that beauty is bound to transience: a flower is beautiful because we know it will soon be gone.

In terms of the quote, I’ve noticed that a number of great works of art are essentially scenes of horror, yet their beauty mediates or even transforms the horror. One of my favorites is Bernini’s The Rape of Proserpina (Persephone), in the Villa Borghese in Rome. You can see the dimples where Pluto’s hand presses into her thigh. It’s a rape scene, but Bernini has turned marble into living flesh. It’s shockingly beautiful.

The Rape of Proserpina (detail) by Bernini.

Photo credit: Alvesgaspar (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Art, whether in sculpture, painting, film, or literature, makes the horror of the world bearable by portraying it in a beautiful way, for example, Hokusai’s iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa, about to engulf fishermen, or The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Delaroche, portraying the execution of a 16-year-old girl. But the painting is so beautiful: the dress, the color, and the exquisite translucence of her skin. All these somehow mediate the horror of the world by rendering it beautiful.

Essentially, I think life itself is sublime. It’s full of horror, pain and suffering, and yet so beautiful at the same time.

You posit that the sublime reveals the fracture that has been created between man and nature, between infinite and finite, between the immeasurably large and the incredibly small. I feel like adding between the Divine and the earthly. Isn’t this also what romantic love does: recognizing the Divine or sacred in another person? And doesn’t true art do something similar, giving us a glimpse of something larger than ourselves that transcends and connects us all?

When I think of the divine, it suggests something sacred and greater than us, something transcendent, as opposed to the earthly, which is grounded in terra firma. For me, there is indeed a connection between sublime art and falling in love. In both, we’re transported and brought into contact with something bigger than us. When we fall in love, it feels as if we’re experiencing something greater, not only than ourselves but even greater than the other. I think it was Plato who said that love is the ladder to the divine, meaning that it is a portal to the transformative experience that you’re referring to.

In both love and art, we recognize something beyond ourselves, something numinous, sacred, and transcendent, which reminds us of how small we are in comparison. This makes me think of the late great Peter Cook. He used to say that when he went for a walk in the countryside at night, in complete darkness he’d look up at the thousands of stars and think: “How insignificant … they are!”, which I thought was very funny. It is the exact opposite of what your question refers to. There’s something very refreshing about feeling part of something much greater. At times it can be terrifying, but at other times deeply comforting.

The importance of paradox

In your 2014 paper Influences on my clinical practice and identity: Jungian analysis on the couch, you quote Jung saying: “The paradox is one of our most valued spiritual possessions, while uniformity of meaning is a sign of weakness… only the paradox comes anywhere near to comprehending the fullness of life”. With the benefit of your subsequent experience, what are the different ways in which you feel this applies?

I think we’ve just touched on this with the paradox of how beautiful and ugly life can be. One of the things I love about Jung is that he acknowledges the mysterious. He’s not afraid to explore it and truly values paradox. He loves to look at things from different perspectives.

We have to hold that same tension in our work, because most patients want cognitive closure. They want clear, certain answers and direction, putting enormous pressure on us to say what’s wrong with them and what they should do. But we have to hold that tension and not allow it to collapse into some kind of premature, misfounded solution, simply because their anxiety stirs our own.

Hillman writes beautifully about analysis as a relationship between soul and spirit. He preferred this poetic language rather than talking about Self and ego. He saw analysis as soul-making, which relies on uncertainty. He associated the word soul with feminine, soft, and deep, staying close to death and living in imagination and religious thought. Soul abides in fantasy: the dimension of the Self that remains in touch with mystery and uncertainty.

Spirit, by contrast, he saw as a facet of the ego: spirited, phallic, sharp, certain, task-driven, penetrating. He comes up with this beautiful line, saying that soul is water to spirit’s fire, and that “soul is like a mermaid that beckons spirit into the depth of passion to extinguish its certainty”. For me that describes analysis itself, for we are trying to invite our patients into a committed, intimate relationship in order to show them that extinguishing the certainty of the ego is the way forward.

It’s the opposite of CBT, which is all about spirited ego solutions. Those can certainly help at times, but I love Hillman’s poetic way of describing how important uncertainty is. Paradox is all about uncertainty, looking at life from different perspectives.

Kalsched noticed that the antonym of symbolic is diabolic. I thought that’s fantastic, because analysis depends on the symbolic position. Symbol means “to bring together”. Analysis is about bringing together diverse perspectives, looking at life from different angles, welcoming diversity and challenging our views.

Diabolic, by contrast, means “to split asunder”, and, interestingly, also means “of the devil”. This splitting lies at the heart of fundamentalism, both religious and political, where diverse opinion is not welcome. In fact, if you don’t hold with the established view, you’re seen as a threat.

Temporality, and breaking of the frame

In your 2012 paper on Terminating Analysis you talk about temporality, and analysis ending with a breaking of the frame. What do you mean by this?

This idea comes from Gilda De Simone and Matte Blanco. Gilda De Simone wrote about temporality, suggesting that our sense of time in analysis reflects the depth of our engagement with the unconscious and its primary processes. If you asked me how long I have been seeing any of my patients, I would not have a clue: six, eight, maybe ten years? I honestly do not know. It is not something I count. But when a patient says, “Do you know you have been seeing me for eight years?”, De Simone describes that as an important moment, what Flournoy calls an acte de passage, a point when unconscious material becomes conscious. For De Simone, this awareness signals something significant: the beginning of the end of analysis. Meltzer says that awareness of temporality, of the nature of time, marks the threshold of the depressive position. I thought that’s fascinating, because I have also noticed this when a patient becomes aware of how long we have been seeing each other.

It also made me think about how interesting temporality is. Sometimes fifty minutes pass like five, and sometimes five minutes feel like an eternity. There is a real distortion of time. This links to Matte Blanco’s, and originally Freud’s, idea that there is no time in the unconscious. For a traumatized patient, a trauma that occurred thirty years ago can feel as though it is happening now and is about to happen again, because past and future become condensed into the present moment. Clinically, this helps to understand the state of mind of traumatized patients. It often feels to them as if the trauma is happening right now, even though it belongs to the past. That is what I mean by temporality, and why I find the idea so interesting.

In terms of breaking the frame, one thing I’ve realized from working in China is that many analytic principles are Daoist in nature. Both Daoism and analysis are based on the principle of non-action. Abstinence and the analytic position are about not giving advice, not recommending action, not agreeing to action, holding the tension of opposites, and resisting cognitive closure.

When a patient says that they’re thinking of ending analysis, 99% of the time I treat it like any other piece of data. In other words, I ask myself what it means. Is it because I just had a long break and the patient wants to retaliate? Is it because they didn’t like what I said last session? Is it because they are frightened of becoming dependent on me? Is it because it’s getting difficult and they don’t want to face painful feelings? Is it because they really want to leave their husband but can’t, so they try to leave me instead? Is it because they are testing me to see if I care, to see whether I will let them go? In all these cases, I don’t agree that they should leave.

There are many possible interpretations for why someone wants to end analysis. But there is that 1% or even 0.1% of the time when I might say: “Yes, I think you’re right. I think this is the time we should be thinking about an ending. Maybe we need to think about a date.” At that moment, you’re breaking the frame, because you’re agreeing to action. Many analyses end with that inevitable and necessary breaking of the frame.

Eros and eroticized trauma

In 2025 you co-edited with Luisa Zoppi a book called The complexity of trauma: Jungian and psychoanalytic approaches to the treatment of trauma. You contribute a profound and deeply moving chapter on Eroticized trauma and its manifestations in the transference. One of the things that stood out is the way you broaden the term “sexual abuse” to include experiences that people might not usually associate with it, for example the premeditated physical beating of a child. Could you speak to that briefly?

The reason I say this is because there’s a huge difference between a parent who, at the end of their tether, loses control, slaps a child, and immediately feels remorse, and a parent who plans and enjoys punishment. I’m talking about parents who say, “Wait till your father gets home”, letting the child suffer hours of anxiety, or a father who says, “Go upstairs and wait for me”, then gets his belt and tells the child to pull their pants down before beating them. That kind of premeditated punishment is, I believe, sexual abuse. Why? Because the parent derives sadistic pleasure from it. And as we know from Freud, all pleasure has a sexual root. They’re getting sadistic sexual pleasure from beating their child, which for me renders it a form of sexual abuse.

In the same chapter, you describe Eros as a force which connects, and eroticization as a creative form of repetition compulsion.

I’m referring to something I’ve seen often, which is how one of the primary defenses is to eroticize or sexualize trauma. By primary defenses, I mean defenses of the Self against overwhelming experiences arising from the internal and external world. The most common ones Otto Kernberg described are projection, projective identification, withdrawal, omnipotence, splitting, and denial. Later, Nancy McWilliams added some valuable ones: dissociation/dislocation, somatization and sexualization.

Secondary defenses are defenses of the ego against the unconscious. These develop after language and after the ego is more fully formed. They include repression, regression, sublimation, and intellectualization.

I’ve noticed in many patients an eroticized trauma. Those who subscribe to BDSM practices in adult sexuality nearly always reveal an eroticization of trauma. For example, if a child is beaten by a parent, it can be a traumatic experience of pain, shame, and humiliation, an experience which is totally out of their control and overwhelming. The unconscious is very ingenious, and can invert that so that in adult life that early experience is turned into something exciting and pleasurable, now under the patient’s control and power. One example is being spanked. The unconscious performs a fascinating switch and reversal, turning trauma into erotic excitement.

How do you understand Eros in its positive aspects as well as in its relationship to trauma?

Eros is a central part of Jungian theory. Jung describes a pair of opposites: Eros and Logos. Eros is the psychological feminine principle of relatedness, connection, and feeling. It is essential in making any kind of relationship. Logos, by contrast, is the more masculine principle of thinking, problem solving, and reason.

For Jung, Eros is not just sexual. It includes anything that tries to make connection and relationship. In its positive aspect, it is essential. We cannot have relationships or answer questions of the heart unless we are connected to Eros, the erotic. The sexual is only one aspect of it. Eros, in that aspect, is very positive.

In the chapter, I tie this to thinking about erotic transference and countertransference. I am very grateful to an analyst called Blum, who corrected something that has needed correcting for some time. Until the early 70s, when Blum wrote his seminal paper on eroticized transference, erotic transference had always been seen as something negative, defensive, and controlling. But he argued that there must be some forms of erotic transference that are positive and healthy. After all, love is an important part of life.

This connects with Jung’s insight that there are only two dynamics in relationship: love and power. Where love is prominent, the need for power and control is diminished. Where power is dominant, love is lacking. I see this in patients who constantly check their partner’s phone trying to control them, keeping tabs on them. This is not love; it is power, a wish to control. The same applies to eroticized transference. Blum introduced the idea of eroticized transference and countertransference as a form of power and control. If a patient is being seductive, sexualizing the interaction, making you uncomfortable, or suggesting meeting outside sessions, this is not about love. It is destructive, meant to destroy the analysis with no regard for your other relationships. It’s about control and power. Eroticized transference describes that type of dynamic accurately.

But if you’ve been working with someone for many years, and you’ve been through an incredibly rich, valuable, dedicated process with challenging experiences for both of you, then it is natural to reach a point of mutual appreciation, affection, concern, and care. These are feelings of love, not sexualized or eroticized love, but gratitude for what you’ve shared together. That, as Blum says, is erotic transference and countertransference. It’s a more positive, healthy experience, guided by love rather than control and power.

Freud’s cancer

In 2013, you contributed the first chapter, Freud’s Cancer, to the book The topic of cancer: New perspectives on the emotional experience of cancer, edited by Jonathan Burke. Subsequently the Freud Museum turned your chapter into a podcast. Could you tell us how the book came about and how you came to write that opening chapter?

This came about because of a really interesting conference on cancer, which Jonathan Burke organized at the London Centre of Psychotherapy. He was looking at cancer from several perspectives: how to work with a patient who is dying or has cancer and how do analysts manage their own cancers and terminal illness? It was a very moving and fascinating conference.

During one of the discussions, I made a throwaway remark on how Freud’s theories changed after he developed cancer of the palate, after which began an awful period of suffering. He endured sixteen years of terrible pain and had over thirty operations. This had a huge impact on him personally and on his theories. I noticed that he stopped writing about the pleasure principle and began introducing the death drive. His work became much darker.

As a result of this comment, Jonathan Burke asked me to write a chapter on Freud’s cancer and its impact on his life and theories for his book on the conference. The Freud Museum heard about it and really liked it. They invited me to give a lecture at the Freud Museum in London, where Freud used to live, and it was later turned into a podcast for the museum.

The Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP) in London

You did your training in London at the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP), founded by Michael Fordham in 1946, who established the developmental school of Jungian analysis. Could you tell us what’s distinctive or special about the SAP’s approach?

One distinctive feature of the SAP’s original Jungian analytic training is the requirement to be in four-times-a-week analysis for many years. You also have to see two training patients four times a week to qualify. This is different from most Jungian trainings around the world, which require a frequency of once or twice a week. It means you enter into deep, intimate, long-term analytic relationships.

Theoretically, what makes it different is Fordham’s contribution. He was the first Jungian to integrate psychoanalytic thinking into analytical psychology. He worked at the Tavistock, alongside Meltzer and Winnicott, and drew from child development and child analysis, as he analyzed many children himself. Much of his theory came from clinical observation rather than abstract theorizing, which made it more scientific.

When I trained, we didn’t just read Jung, Hillman, von Franz, and Neumann. We also studied Freud, Klein, Bion, Winnicott, Meltzer, Bollas, Bowlby, and many others. I’m so grateful for that, because it allows a much wider perspective. Some Jungians dismiss Freud, which I think is a shame. I think to be truly Jungian means learning from everyone. In his four stages of analysis (catharsis, elucidation, education, and transformation), Jung incorporates ideas from the Church, Freud, and Adler.

The third distinguishing feature is the focus on transference and countertransference. Fordham realized that the most therapeutic factor in analysis is the relationship itself. You have to be in it, examining the transference and countertransference. I’ve noticed in supervising trainees worldwide that there’s often a tendency to focus on intrapsychic or archetypal interpretations rather than the transference and countertransference. That’s a real shame because it places the analyst as an observer rather than a participant. Studying the transference means looking at the impact the patient has on you and you on them. It’s much more emotionally intense, authentic, and real.

That’s what defines the developmental school, not just the SAP. Together with San Francisco, it is the oldest Jungian training program, founded even before Zürich.

Analytic training

You’ve compared analysis to jazz and stated that we need to be grounded in the rules before we can improvise, but that it is often the improvisation which makes the piece. How much do talent, predisposition, and experience, both personal and professional, influence an analyst’s skill and art? Can they, to some extent, compensate for the limits of formal theoretical instruction of the rules?

This makes me think about Jan Wiener and Tom Kelly, who wrote about what they called character and competencies. To be an analyst, you need two things. You need the right character and personality. Then, with that, you can develop skills and competencies over time, learning your craft.

Some people do not have the necessary character or personality. You have to be able to form a committed relationship that lasts years, have patience, suppress your personality, observe the rules of abstinence and non-action, be dedicated, compassionate, curious, authentic, and love the truth. Not everyone has these traits. Even if you have them, you still need to develop your craft. As Warren Colman says, you have to hone your skills. This is the starting point from which you can learn many things. It is like playing music: many people can dabble, but to be a professional musician, you need a skill set and you have to work at it to develop it.

When you talk about the limits of theoretical or formal instruction, it reminds me of Bion’s vertices. Bion said one problem in analytic trainings is that we are only taught the scientific vertex, which is rational, reductive, and focused on the past. It’s about understanding where the patient is now by looking at their early childhood experiences, attachments, and traumas. It’s quite paternal, its main idiom being interpretation, putting words to feelings to create meaning.

But that is only one required vertex according to Bion. You also need the aesthetic vertex, which is about the here and now, the sensual experience of being in the room with the patient. This vertex is more maternal. Its idiom is containment. It includes awareness of sharing the objects in the room, the way the light plays on the wall, what you and the patient are wearing, how you both breathe and smell. All these aesthetic details are part of the here-and-now sensual and aesthetic experience.

Surprisingly for a neo-Kleinian, Bion also talks about the spiritual vertex, which is much closer to Jung’s ideas. This is synthetic, about looking to the future: in which direction is the Self taking the patient? It is open to existential, philosophical, and ethical questions about the meaning of life, what happens after death, and whether there’s a God.

The other thing that comes to mind is Winnicott’s comment that you do not really start being an analyst until at least fifteen years after qualification. I think there is a lot of truth in that.

To conclude, is there a quote from Jung that speaks to you personally above all others?

“That the greatest or most important problems in life are fundamentally unsolvable. They cannot be solved, but they can be outgrown.”

That insight has been profoundly true in my experience and deeply helpful in my work. Patients often come in with a burning question or an unbearable problem they feel must be solved. Then, a year or two later, I might ask what happened to that terrible problem that brought them into analysis, the one that caused so much suffering. And they say: “Oh, that’s not important anymore. We need to talk about this new thing.” The problem was not solved; it simply became irrelevant. It was outgrown. Something new emerged that demanded attention and growth.

That realization was invaluable early in my career. At first, I thought my task was to find clever, penetrating, mutative interpretations to solve the patient’s problem and give them direction. But I came to see that this is impossible, and it is not what the work is really about. Our task is to stay present, to be emotionally available, to hold the patient, and to help them find their own way to live, change, or outgrow what once seemed unbearable.

It is about the journey, not the end goal.

Exactly. We do not need to arrive at Ithaca just yet.

Thank you so much, Martin, for offering us a glimpse into your research and clinical work over the past twenty years. Reading your papers and book chapters has been both thought-provoking and inspiring, and I’m very grateful you took the time to share some of your insights with us today.

Interview conducted by Peggy Vermeesch – November 2025

References

Martin Schmidt

Martin Schmidt is a Jungian Training Analyst at the Society of Analytical Psychology in London, working full-time in private practice. He started his career as a psychologist in psychiatric rehabilitation and has been actively involved for many years in training the first Jungian analysts in Russia, Ukraine and now China. From 2016 to 2019, he served as IAAP Honorary Secretary, and as Regional Organizer for Central Europe, responsible for organizing the training and examination of Jungian analysts in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. He continues to serve as IAAP Liaison for Serbia.

Martin Schmidt is a Jungian Training Analyst at the Society of Analytical Psychology in London, working full-time in private practice. He started his career as a psychologist in psychiatric rehabilitation and has been actively involved for many years in training the first Jungian analysts in Russia, Ukraine and now China. From 2016 to 2019, he served as IAAP Honorary Secretary, and as Regional Organizer for Central Europe, responsible for organizing the training and examination of Jungian analysts in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. He continues to serve as IAAP Liaison for Serbia.

Learn more

- Exploring paradox in the analytic process—an interview with Martin Schmidt, conducted by Peggy Vermeesch, (also available as a video interview)