A strange and luminous dream has risen from the depths: Orpheus stands before an assembly. He seems to speak, and a calm settles over them. Just as everything seems to be settling down, Eurydice enters, bearing lit candelabra—branched candle holders that she realizes are none other than the hands of Orpheus.

In this symbolic, contemplative essay, Claire Droin blends dream interpretation, myth, and Jungian psychological themes in a reflective exploration of the archetypal meaning of the hand, using a dream image as a launching point for deeper psychological insight.

French version of this article

AI-generated image.

On this page

- Introduction

- Hands and light

- Shadow aspects of hands

- Losing one’s hands

- Transformation of hands

- Conclusion

Introduction

In the dream, the hands of Orpheus have become torches that illuminate but are also separated from him. No longer hands that touch or play music, they exist as objects of light. The hands of Eurydice, meanwhile, present these objects to the world and offer their fire to the collective gaze.

What struck me most upon waking was that these hands were revealed—as if, in detaching themselves, they became bearers of a meaning greater than their own. It was then that a question arose, simple yet insistent: What do the hands say?

I invite you to contemplate this image from the dream, as if it had quietly called us to offer our own hands to our consciousness. We will explore the hand’s many symbolic dimensions: its ties to light and shadow, its loss, and its transformation.

Hands and light

In this dream, the hands of Orpheus have become lit candelabra—branched candle holders. This transformation invites reflection on the symbolic connection between hands and light. Two opposing images emerge:

The hand of glory

The « hand of glory » is the image closest to the one in the dream. Historically, it is the severed hand of a corpse whose fingers bear flames or candles. Transformed into a magical object, it illuminates the space while paralyzing those within it. Its use is documented from the 15th to the 18th centuries in certain European countries, and appears similarly in a 16th-century Mexican Amerindian tradition.

Here, the light is not used to animate or warm, but to freeze. In this image, the hand becomes an object, an instrument of immobilisation.

The hand of grace

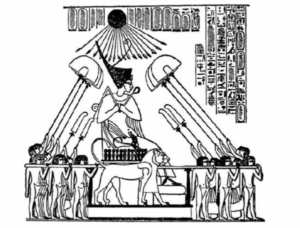

In contrast, ancient Egypt depicts the sun god Aton as a disc from which rays extend, ending in hands. These hands are rays of light themselves, symbolizing the creator’s transmission. The sunbeam becomes a gesture that bestows life and divine power, as Carl Gustav Jung illustrates in Symbols of Transformation (CW5).

The life-giving Sun: Amenophis IV on his throne (Relief, Egypt). Drawing from Budge, The Gods of the Egyptians, II, p. 74. Reproduced in Jung (CW5, para 148).

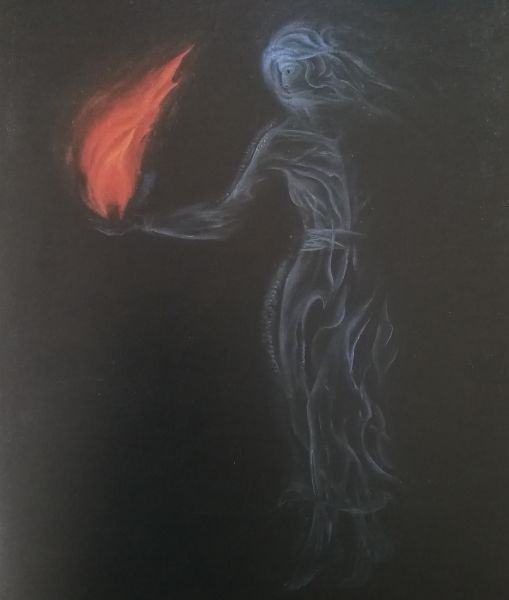

Illustrating the same dynamic, Marie-Louise von Franz commented on Peter Birkhäuser’s painting The Flame Dancer that the feminine’s task is to « mediate and bring to man the divine fire and its creative power » (Birkhäuser, 1981/2025).

These two figures—the severed candle-holding hand and the radiant hand—can be seen as two poles of the same psychic reality: the hand contains within it the ambiguity and power of fire. The hand, bearer of fire, can both petrify and enliven, dominate and transmit.

The Flame Dancer by Peter Birkhäuser. Oil (1974), lithography (1975).

The hand is linked to light, yet light cannot exist without darkness. We will now explore the other side—the shadow of the hand.

Shadow aspects of hands

Surprisingly, Orpheus may come from the Greek word orphen, meaning « darkness ». The hands of Orpheus also carry shadows. Shadows of hands appear notably in cave paintings and in the art of Chinese shadow puppetry.

Negative hand from Tibiran Cave (Hautes-Pyrénées, France). Photo credit: FM Callot

Jung associated the image of the cave with the dark world of the unconscious, a primordial, subterranean place where the silent unfolding of the psyche takes place. In Paleolithic parietal art, handprints—both positive and negative—adorn the walls. Whole hands or mutilated ones, like those at Gargas (Hautes-Pyrénées, France), stand as signatures. They hold nothing, bear no attributes, reveal nothing; they are pure presences—traces of being left in matter and time.

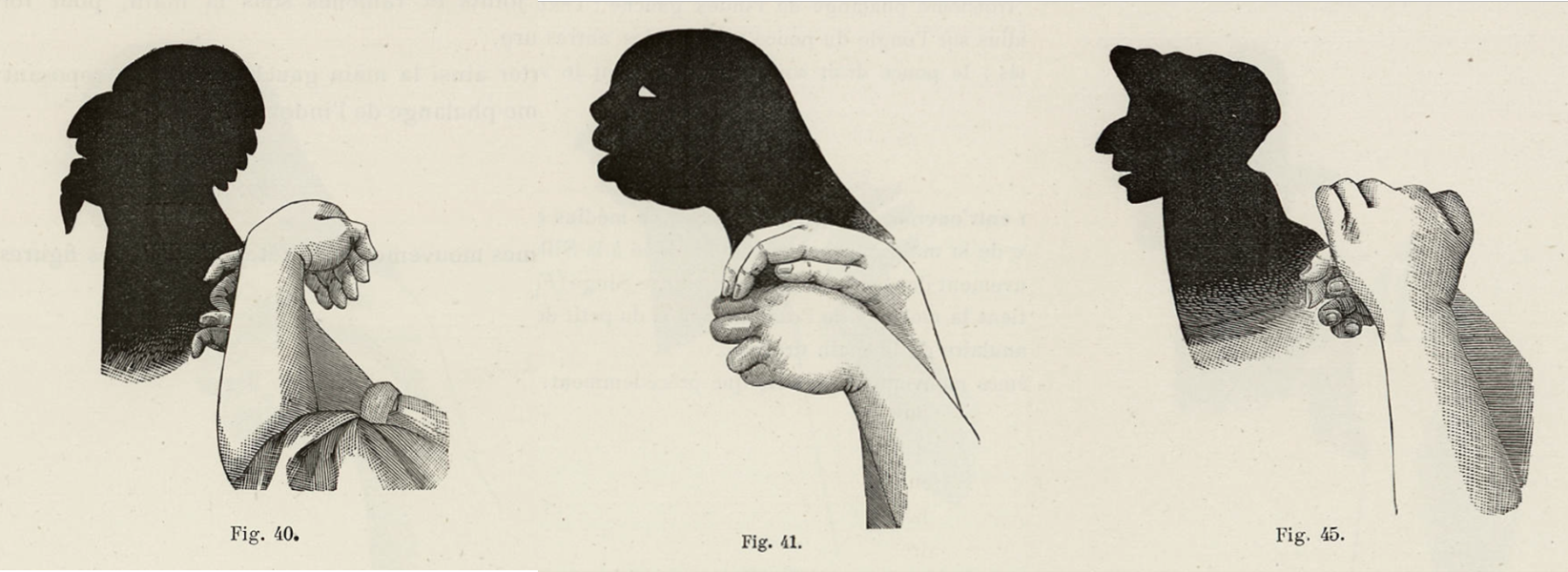

Furthermore, shadows cast by placing one’s hands in a beam of light (ombromania) create shapes, figures, and characters. After being used for religious purposes to evoke the souls of the dead, this traditional practice became a form of popular entertainment in both the East and the West, where, in the 19th century, it was used to caricature personalities.

Illustrations of hand-animated silhouettes by Victor Effendi Bertrand (1892).

Thus, the shade and shape of the hands would carry individual traits. This is also emphasized by Carl Gustav Jung in his introduction to Julius Spier’s book on psycho-chirology:

« The totality-conception of modern biology which is based on the evidence of a host of observations and research, does not exclude the possibility that hands, whose shape and functioning are so intimately connected with the psyche, might provide revealing and, therefore, interpretable expressions of psychical peculiarity, that is, of the human character. » (Jung, 1944, p. xi)

The hand is a marker of personal identity. In the dream, Eurydice recognizes Orpheus’s hands, even though they are separated from him: the hand retains its identity, even when severed.

Losing one’s hands

The hand is synonymous with action, doing, and responsibility (we wash our hands of something to be rid of it). It is also an instrument of connection, through gesture, exchange, writing, and art. It embodies this dual function of doing and binding, and its loss is a sign of rupture.

Rupture in the ability to act

Historically, hand amputation was used as a way to neutralize wrongful actions. It deprived the individual not only of their ability to act but, more importantly, of their capacity to do harm. This practice existed as a form of punishment across many cultures.

In the ancient world, the Code of Hammurabi (circa 18th century BCE) prescribed amputation for thieves and counterfeiters. In the Quran, the punishment is mentioned for thieves in verse 5:38 of Surah al-Ma’ida: « As to the thief, the male and the female, cut off their hands as a punishment for what they have done, an exemplary punishment from Allah. » Over the course of Islamic history, this verse has been interpreted in various ways, sometimes quite literally. In the Bible, a similar idea appears, though in a more metaphorical form. Jesus himself uses the image of amputation to convey voluntary renunciation of evil: « If your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away from you. » (Matthew 5:30).

In all these cases, losing a hand makes the wrongful act impossible. It disarms the individual, preventing action, but also leaves them vulnerable and dependent. This is vividly illustrated in the Brothers Grimm tale The Handless Maiden, where a young woman’s own father cuts off her hands. The act strips her not just of her ability to act, but of her autonomy. She becomes a wandering, passive figure, unable either to grasp or to defend.

And yet, this mutilation sets the stage for transformation. Through her experience of helplessness, the young woman encounters love, motherhood, and faith, and in the end, her hands are restored. The story suggests that losing one’s hands can become a passage toward reclaiming one’s own power.

Rupture in the ability to relate

The loss of one’s hands affects more than just « doing »—it also strikes at connection. The hand is the very organ of touch and contact, and its absence profoundly disrupts the ability to relate to others.

In a more contemporary tale, Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands presents a figure with extraordinary creative power, yet unable to connect with others. His hands, made of blades, sculpt with brilliance but cannot touch or caress without causing harm. The story highlights the link between the power to create and the vulnerability of human relationships, between exclusion and self-acceptance.

In the dream, Eurydice presents Orpheus’s hands to the assembly. Yet Orpheus is her husband—the one to whom her hand was given in marriage. This seems to seal their bond, their union of spirit even in death. It is the feminine (connection, interiority, eros) that makes visible what the masculine (action, creative drive, logos) could not reveal on its own: the fire. Orpheus’s hands are sacrificed in the process, yet it is precisely through this loss that transformation brings clarity.

Thus, through these examples, the hand reveals itself as a synthesis of opposites: action and relationship, masculine and feminine, power and vulnerability. It also becomes clear that the loss of hands marks a passage—a journey of psychic transformation, a true metamorphosis.

Transformation of hands

When it undergoes transformation, the hand no longer acts or engages in the same way. Yet it preserves something of its character and remains recognizable, even in a different form.

In general, the hand transforms over the course of life, changing with time. It ages, bears marks, carries the traces of the past (like the stigmata on the hands of Christ), and reaches toward the future (as seen in palm reading or chiromancy).

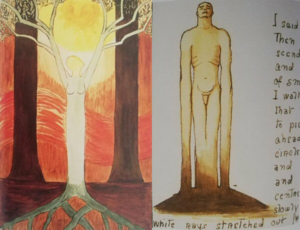

Through metamorphosis, we encounter both the sense of loss and the experience of freedom. In Visions: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1930–1934, these two aspects are visible in the drawings of Christiana Morgan, a patient of Carl Gustav Jung:

- The hands transform into branches and leaves, rising toward the sky, free.

- The hands sink into the earth, taking root, as if imprisoned.

Drawings of Christiana Morgan (Douglas, 1998).

In the dream, Orpheus’s hands are not merely transformed—they have « changed hands ». Orpheus and Eurydice are joined by the bonds of marriage. Their hands are intimately connected.

Metamorphosis entails a form of dispossession: the hands no longer belong to Orpheus, yet they retain his identity, recognized by Eurydice. Even when lost or transformed, the hand can continue to carry meaning. It may become a symbol to pass on, a light to share, a memory to honor—like Orpheus’s hands, lifted by Eurydice for all to see.

Conclusion

The dream offers no answer, yet it presents a striking image: hands transformed into candelabra, revealed to the world. They are no longer hands that act, that touch, that play—they are hands that shine and are displayed for all to see.

In their light as in their mutilation, hands speak of our power to act, but also of our fragility. They reveal who we are, what we have lost, what we still carry, and perhaps what we have that we can pass on. To present our hands, as in this dream, would be a way of taking a step toward self-awareness—of accepting that, through them, something continues to speak of us.

Drawing on this allegory, we have observed how hands—first as light, then shadow, then absence, and finally through metamorphosis—become a message. The dream seems to suggest that what is lost in action and in connection can be reclaimed through the power of fire and image, of spirit and symbol.

Original Article by Claire Droin,

translation by Claire Droin & Peggy Vermeesch.

September 2025

References

- Birkhäuser, P. (2025). Light from the Darkness: Paintings by Peter Birkhäuser, Commentary by Marie-Louise von Franz / Licht Aus Dem Dunkel: Malerei von Peter Birkhäuser, Kommentar von Marie-Louise von Franz. Daimon Verlag. (Original work published 1981)

- Douglas, C. (1998). Visions: notes on the seminar given in 1930-1934.

- Jung, C. G. (1944). Introduction by C. G. Jung. In J. Spier, The hands of children: An introduction to psycho-chirology (pp. xi–xii). Kegan Paul.

- Jung, C. G. (1956). Symbols of transformation. CW 5.

Claire Droin

Located in Villefranche-sur-Saône, north of Lyon, France, Claire Droin works as a psychopractitioner and leads workshops aimed at exploring and enhancing self-awareness.

Claire is interested in C.G. Jung’s thoughts and vision of the psychic world, drawing inspiration and comprehensive understanding from his writings.

Through her practice and her contributions to Espace Francophone Jungien, Claire is committed to helping individuals gain a deeper understanding of their true nature.

For more information, visit her website PBAtitude.

Articles & interviews

- The hands of Orpheus

- The Decline of Sexuality: An interview with Luigi Zoja

- Paranoia or Lucid Madness

For a list of articles and interviews published in French, visit Claire Droin’s page on EFJ.